When the number of cranes outnumber the skyscrapers the country’s economy is set to boom. It is an economist’s rule of thumb and not a bad way of assessing potential growth. We dig a little deeper too. Our analysis of 140 developed and emerging countries shows potential GDP growth remains attractive for both China and India. But Brazil and Russia (the other half of the BRICs marketing moniker) have disappointed. “BRICs” has had its day.

Russia ranks poorly with respect property rights and the burden of government regulation. Brazil ranks towards the worst in the world for the efficiency of its goods and labour market and its “macro-economic environment” ranking has slumped resulting in it falling from 47th to 69th in our analysis, as Dilma Rousseff has presided over an economic disaster.

India and China continue to demonstrate huge potential for GDP growth. In China, ranked 21st in our analysis, the large, cheap labour force of the 1980s has evolved into an ageing population with rising production costs, hampering its rapid growth. But GDP per head remains low by western standards and China’s reform of its capital markets (despite ranking 1st for “market size”, China only ranks 54th for “financial market development”) should continue to assist in closing the gap.

India, under the leadership of Narendra Modi, has leapt upwards relative to other countries with respect competitiveness and in our analysis it now ranks 11th. Its overall competitiveness ranking is let down by its performance in the “Basic Requirements” category where it ranks only 91st for the “macro-economic environment” and 84th for “health and primary education”. Improvements can also be made in “technological readiness” (120th) and “labour market efficiency” (103rd). India’s overall competitiveness ranking is being propped up by “market size” where it is 3rd out of all the countries analysed.

Huge populations provide opportunity. India and China continue to demonstrate potential to grow. But in both countries, Government bureaucracy ranks in the top 10 problematic factors for doing business. It takes more than 28 days to start a business in India, involving 12 procedures. China has 1 fewer procedure but it takes more than 31 days. To be competitive, this needs to be reduced heavily, along with government bureaucracy.

India has huge strides to take in its education system. Maybe somewhat surprisingly it ranks only 105th with regard secondary education enrolment though the quality of the education system ranks significantly higher (43rd). Primary school enrolment of 93.1% of children ranks India mid-table. It must improve this to transition its economy towards further growth.

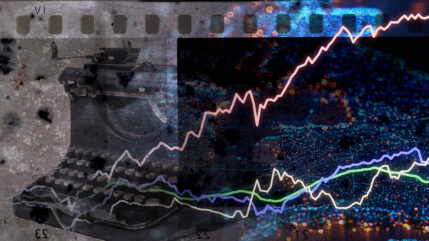

Our analysis, based on the relationship between competitiveness and GDP per capita, shows that India could increase its GDP per capita from $6,200 to $22,200 and that China could increase its GDP per capita from $14,200 to $35,500. These represent huge increases and indicate that, given current levels of competitiveness, both India and China are punching below their weight. The key for India and China will be to continue to improve across all competitiveness factors at a superior rate to other countries.

I saw hundreds of cranes in the second tier Chinese cities when I was there in 2014 (far fewer in the well-developed, larger cities of Shanghai and Beijing). I plan to spend plenty of time looking upwards when I visit India later this year.

Courtiers uses the World Economic Forum (WEF) Global Competitiveness Index (GCI) as the basis for its analysis. The GCI takes 114 different factors to score each country with respect competitiveness. The factors are grouped into categories such as “health and primary education”, “market size”, “innovation”, “business sophistication”, “macro-economic environment” and “financial market development”. Each country is ranked within each factor. Courtiers has been analysing the WEF data and producing an annual research report on the strength of the relationship between competitiveness and GDP per capita for 9 years. The COURTIERS analysis produces a country ranking based on potential GDP growth, driven by the relationship between competitiveness and GDP.