At the Client Seminar last December, I talked about the Chinese funding of large physical infrastructure projects in key locations. This included ports, roads, bridges and power stations. But what about digital infrastructure? And what’s China doing with it?

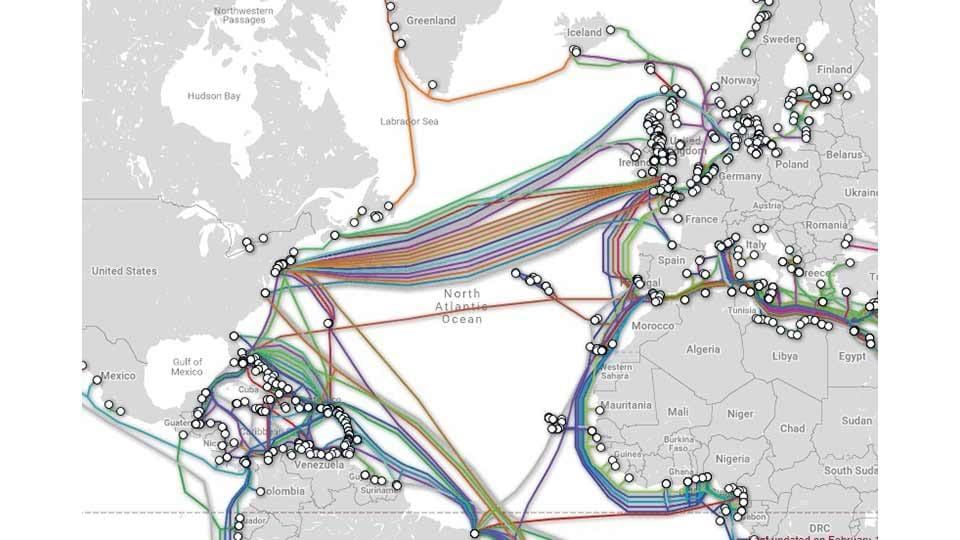

Infrastructure is not always visible. Over 95% of internet traffic (including your text messages and web searches) travels in fibre-optic cables buried under our oceans. The idea of digital messages bouncing off satellites isn’t so real after all. At least not for most of us.

Who owns these cables under the sea and where do they connect? It was in the 1850s that the first cables were laid carrying telegraphy traffic. The British dominated the cable laying market in the 19th century and worked on connecting the British Empire to create a global network.

By the 1870s London was connected to New Zealand using cables via Bombay (now Mumbai), Singapore, China and Australia. Transatlantic cables dominated development (the North Atlantic Ocean area was seen as the most important market) and later, in the early 20th century, the first telegraphic cables were laid across the Pacific.

Source: US & Western Europe submarine cables, Telegeography, 2019

Today, there are over 400 cables under the oceans and they connect almost every landmass from Greenland to Canada and from Japan to the Philippines. Antarctica is the only continent not connected and messages to and from Antarctica are relayed via satellites. The cables are typically owned by a consortium of global telecommunications companies, but the promise of faster internet speeds means there are many interested parties, including governments.

China’s “Belt and Road” project is financing and building infrastructure in its neighbouring countries and, increasingly, globally. The digital version of “Belt and Road” is much less visible but is becoming more important. A 2015 Chinese white paper notes the need to build cross–border optical cable networks more quickly and to plan trans-continental submarine cable projects, all as part of the “information Silk Road”.

Last year China connected to Pakistan in a two year long 820km cable project. The project was financed by a Chinese bank (Export Import Bank of China, EXIM) while Huawei (the Chinese telecommunications company) was responsible for engineering and construction. The project is owned by the Pakistan government.

Other countries are wary. In late 2018, Australia offered alternatives to the project agreed to by the Papua New Guinea government. That project was another EXIM-Huawei tie up and was intended to connect the communities across Papua New Guinea, eventually connecting to the Coral Sea Cable System which this year will connect through to the Solomon Islands and Australia. It was the second time in a matter of months that Australia had offered a Pacific Island government an “alternative” solution. The Solomon Islands had originally awarded Huawei the contract to connect them to Australia but the Australians, concerned about the security risks posed by Huawei accessing the network at Sydney, offered to fund and build the project as part of its foreign aid programme.

Some countries have banned Huawei from upgrading 5G networks for fear of government spying. The British dominance is long gone. The world seems to have become accustomed to the US having influence over these undersea cables but no one seems quite ready for the Chinese to have the same influence.

China is building its infrastructure network far and wide to secure both its trade routes and a home for its exports. These projects are financed with Chinese money and require the appointment of Chinese contractors, often using Chinese materials. Risks abound. If the country cannot afford to pay the debt obligations then China can step in to offer a solution, sometimes involving the exchange in ownership of the asset (as happened with the Hambantota port in Sri Lanka). China appears to be setting itself up for potentially accessing digital “ports”.

China is trying to step up a level to compete with the developed world and flex its global muscles whilst gaining leverage over some of its neighbours, particularly those in strategically important locations. Yet its growth is slowing and its domestic demand is slumping which could lead to bigger problems at home.