After 14 years of Conservative leadership, on 4th July, Keir Starmer’s Labour won the 2024 General Election with a massive majority, shifting the electoral map from blue to red.

The last time Labour replaced the Conservatives, they sprung an economic surprise within a few days that nobody saw coming – granting independence to the Bank of England. Just over 27 years later, Labour’s significant centre-left majority offers a potential five years of stability, which is likely the envy of the Western world. You could even argue that Starmer’s victory inspired the French to wish their right-wing resurgence a bon voyage in their own election. But with Labour’s key message offering a promise of change, what lies ahead?

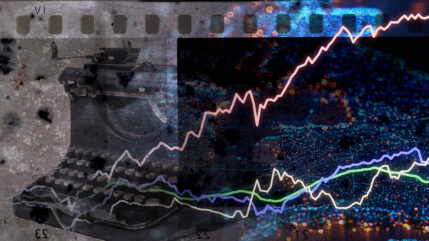

GDP and historical figures

The economic backdrop Labour inherited on 5th July is darker than 27 years ago. In the 1997-98 financial year, government borrowing was 1.1% of GDP and total government debt was 36.7% of GDP. The 2024-25 corresponding figures are projected as nearly triple – 3.1% and 91.7%. However, total government debt was much higher in 1822 (194%) and hit a peak in 1946 at 259%. Economics is often described as the “dismal science”, with economists being seen as pessimists.

“In March 1981, 364 economists, all then present or retired members of the economic staff of British universities, wrote a letter to the Thatcher government criticising its policies which, they said, would ‘…deepen the depression, erode the industrial base of the economy and threaten its social and political stability’. This was after the Q4 1980 figures showed the economy shrinking by -4.1% (annualised).

“Almost immediately after the letter was published the economy began to improve. The rate of decline shrunk during the remainder of 1981 and GDP growth from then until the end of the decade averaged an impressive 3.5% per annum. Not quite the disaster that the great and the good of Britain’s elite economic faculties had predicted.” – Gary Reynolds, CIO, Courtiers.

Whereas in 1997-98, government benefitted from a ‘peace dividend’, the last few years of global tensions mean Labour now faces the opposite situation; the defence budget set to rise to 2.5% of GDP, with net interest projected at nearly £65 billion in 2024-25.

There is much pessimism around these public finances, but it’s misplaced. We are a very, very wealthy nation.

“Government debt to GDP is only slightly above its long-term average. Furthermore, it doesn’t take account of the considerable private wealth that has been built up in this country over the last few decades.” – Gary Reynolds, CIO, Courtiers.

The wider range of challenges facing the new Prime Minister and his cabinet go deeper, as identified by chief of staff Sue Gray earlier in the year. These include:

- the NHS funding gap and social care requirements

- public sector pay negotiations

- local council bankruptcies

- the housing deficit

- a potential collapse of the largest water company, Thames Water

- overcrowding in prisons and the criminal justice backlog

- the schools and university funding crisis

In these financial circumstances, a government elected under the banner of change will soon face tough decisions on tax, spending and borrowing.

“Starmer has listed five specific areas for targeting by his new cabinet:

economic growth

the NHS

crime

education

renewable energy

If Labour can make just small incremental improvements in each and demonstrate that the country is going in the right direction, then it is likely the electorate will trust the new PM with a second term.” – Gary Reynolds, CIO, Courtiers.

Tax planning

Tax was a key attack area for the Conservatives during the election, whose recent record put themselves on weak ground. Labour’s manifesto listed its now-familiar tax-raising plans to:

- reduce tax avoidance

- revise non-domiciled taxation rules

- levy VAT and business rates on private schools

- end the capital gains tax treatment of carried interest

- enact a windfall tax on ‘oil and gas giants’

- increase stamp duty land tax rates by one percentage point on residential property purchases by non-UK residents

The manifesto also said, “We will ensure taxes on working people are kept as low as possible. Labour will not increase taxes on working people, which is why we will not increase National Insurance, the basic, higher, or additional rates of Income Tax, or VAT.” The definition of ‘working people’ was never resolved during the election campaign; both Keir Starmer and Chancellor Rachel Reeves defined it as “people who go out to work and work for their incomes”, but they were vague on whether this included those who had savings.

The manifesto additionally promised to cap Corporation Tax at 25% but was silent on Inheritance Tax (IHT) and Capital Gains Tax (CGT). While these taxes could feature in the next Budget, HMRC’s own estimates suggest any sharp rise in CGT rates would be self-defeating because of ‘behavioural effects’, e.g. people would be reluctant to sell their assets with this tax rise, keeping the gains unrealised.

On the other hand, a month before Rishi Sunak called the election, the Institute for Fiscal Studies published a paper explaining how the closure of three IHT ‘loopholes’ could raise nearly £4 billion a year by 2029-30.

The autumn Budget

Rachel Reeves ruled out an emergency Budget, saying she will give the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) the normal ten weeks’ notice to prepare an Economic and Fiscal Outlook ahead of her presenting her first Budget. Reeves requested an update from the Treasury on the UK’s financial position to present to parliament by the end of the month, announcing on Monday 8th July that “difficult decisions” lay ahead.

In theory, the earliest Budget date could be Friday 13th September (or 18th September to adhere to a traditional Wednesday), but this is unlikely.

On the other hand, a month before Rishi Sunak called the election, the Institute for Fiscal Studies published a paper explaining how the closure of three IHT ‘loopholes’ could raise nearly £4 billion a year by 2029-30.

Labour’s first hundred days

In his speech on the steps of Downing Street on 5th July, Kier Starmer said “the work of change begins immediately.” However, with a tricky summer timeline that includes the House of Commons summer recess, Conference recesses and State Opening, there isn’t much parliamentary time for the government to work with before 12th October, which marks the end of Labour’s first 100 days in office.

In political folklore, this is the period when a new government has the greatest political clout. Given the challenges and expectations of the new government, working up to that point will focus the mind of the Prime Minister and his advisers when reviewing those recess periods and setting a date for their first Budget.

The Chancellor is due to meet with the OBR over the next few days. Focusing on housing, removing planning restrictions and the ever-present need for growth in her first speech to the Treasury on 8 July, Reeves said she would confirm a Budget date before the summer recess for “later in the year”.

Those 100 days are going to be very busy.

“[If Starmer can demonstrate the country is going in the right direction,] perhaps we can look forward to a decade of stability with improved GDP growth, better public services and sound financial management.

“That would be very good for UK equity prices, which reflect the fact that British companies have been battling extreme political instability caused by the party that was historically viewed as the best for the economy and business.” – Gary Reynolds, CIO, Courtiers.