“Buy when prices are low – sell when they’re high.” For investors that’s a holy grail, not a viable long-term strategy.

Imagine you sold your investments in late 2019 when stock markets were high. Then you bought back in at the lowest point during the March 2020 crash, to enjoy the rapid recovery that ensued. You would have timed the markets well.

Or what if you assumed the identity of ‘Peter Perfect’? A study by American multinational financial services company Charles Schwab found that a hypothetical investor, Peter Perfect, who invested $2,000 every year between 2001 and 2021 on the day that the S&P 500 Index was at its lowest point, saw their total $40,000 investment grow to an impressive $151,391.

Peter Perfect confronts reality

Any study or theory on timing investments using past market performance (there are many) is essentially hindsight. And while emulating Peter Perfect would be wonderful, the reality is that timing markets (i.e.: putting your money in and taking it out based on what’s happening in the markets at the time), to maximise returns over time is incredibly difficult, if not virtually impossible.

In fact, when private investors attempt to time markets they tend to suffer more than succeed. A study by the Cass Business School commissioned by Barclays found that compared to a simple buy-and-hold strategy, UK investors’ judgement about when to buy and sell equity funds cost them dear. Compared to a simple buy-and-hold strategy, between 1992 and 2009 the study concluded that what’s called ‘the behaviour gap’ reduced returns by 1.2 percentage points a year and overall returns by 16%.

Explaining ‘the behaviour gap’

The behaviour gap is a well-known term coined by American financial planner, author, speaker and New York Times columnist Carl Richards. It refers to the difference in returns that can result from people making emotionally driven decisions based on market activity – decisions which prove to have a detrimental impact in the long term.

Despite the logical part of our brains telling us to buy low and sell high, our innate human psychology often tells us to do the opposite. A prime example occurred at the start of 2000 when investors joined in the buying spree for technology funds – but alas for many investors only after valuations had already reached exalted levels. The tech bubble subsequently burst in March of 2000 after the NASDAQ Composite Index had peaked at 5,048. This was more than double its value just a year before, leaving those who were late to the party nursing heavy losses.

Conversely, when markets or the price of a particular stock or fund collapse, investors tend to sell to avoid further losses, which means they risk missing out on any subsequent recovery. For instance, during the global financial crisis of 2008/2009 between the end of May 2008 and the start of February the following year the MSCI World Total Returns Index of global companies fell by 23.9% in GBP (pounds sterling).

Anyone who sold out at that point would’ve missed out on a rapid recovery, which saw the market bounce back by 42.5% in GBP between 20/11/2008 and the end of 2009.

Don’t fall for FOMO

Whether it’s fear of missing out (a phenomenon defined today as “FOMO”), which leads to chasing performance, or joining the ranks of panicked sellers when prices are plummeting, investors have a tendency to do the opposite of what would be in their best economic interests. This is often combined with quick-fire responses to short-term gyrations in the market, even though a wealth of empirical evidence shows that this comes to the detriment of investor returns.

The importance of keeping your head while all about you are losing theirs is nicely summed up by one of the giants of modern investing Benjamin Graham, when he said; “Individuals who cannot master their emotions are ill-suited to profit.”

Putting a price on ‘the behaviour gap’

The Cass Business School study put a cost on investors’ tendency to get their timing wrong. It calculated that between 1992 and 2009 the average UK equity private investor turned an initial £100 investment into £255. By way of comparison, it said a simple buy-and-hold strategy would have grown an initial £100 investment into £311. The study concluded that the difference of £56 was down to investors’ tendency to invest more after periods of strong stock market performance, and less after periods of weak stock market performance. The penalty tends to be larger in years with greater average volatility.

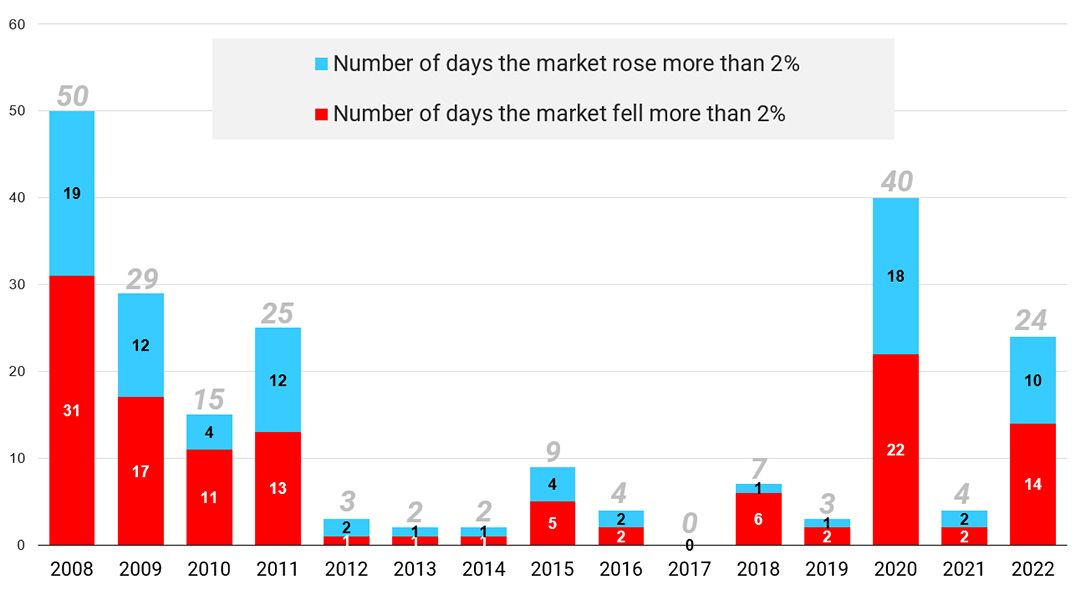

Attempts to time the market are further complicated because as shown in Chart 1 below, the largest jumps in stock markets often happen during periods when market volatility is at its highest.

Source: Courtiers/Bloomberg

Source: Courtiers/Bloomberg

Analysis by J.P. Morgan Asset Management found that between 2002 and the end of May 2022, nine out of the best 10 days for the S&P 500 Index occurred either during the global financial crisis of 2008 or at the start of the Covid pandemic in 2020. This included two days when the market jumped by more than 10%. The market’s worst days are typically interspersed with their best, which is why jumping on the selling bandwagon can mean investors missing out on a subsequent upturn.

The ability of stock markets to recover quickly is confirmed by US independent investment research consultancy Dalbar. It looked at the eight years since 1940 in which the S&P 500 Index experienced a drop of 10% or more and found that in three of those years, the market had recovered within a year and all had recovered within five. This is a subject for another article, but there’s a compelling body of evidence to show that time in the market trumps timing the market, and the longer you’re invested in the market, the greater the probability of a positive return.