Stock market volatility is a fact of life for investors. As legendary US investor Warren Buffett put it; “Unless you can watch your stock holding decline by 50% without becoming panic-stricken, you should not be in the stock market.”

In recent weeks Buffett’s words have gained added resonance as a cocktail of factors have destabilised stock markets and individual stocks. The VIX Index, which is widely used as a measure of volatility and is often referred to as the ‘fear gauge’, has risen steadily since the beginning of the year driven by the conflict in Ukraine, rising inflation and continuing problems in the world supply chain. That said, it remains at less than half the level it reached in 2020 when Covid first arrived.

With volatility back in the news, I thought this was a good time to ask Courtiers Deputy Fund Manager James Timpson all about it.

Q: James, I will start with an obvious question, how is the volatility of a stock market measured?

James: Volatility is a measure of how much variation there is in the price of an asset, or in this case an index. Typically, this variation is measured via a metric called standard deviation. So, an index which has greater movements in its daily or monthly prices will have a higher standard deviation and can therefore be considered more volatile.

Q: How useful is the VIX Index?

James: The VIX index measures the expected volatility of the S&P 500 index, which tracks US equities. It does this by looking at the prices of options on the S&P 500 index. If volatility is expected to be high, then option prices will be higher because there is a greater chance that the options will become profitable.

Let’s say the S&P 500 index is currently at 4,000 and you have a put option on the index with a strike of 3,800. In other words, you have the option to sell the index at 3,800. If volatility is expected to rise, there is a greater chance that at some point the index will fall below 3,800 and you will be able to exercise your option for a profit. Therefore, the option becomes more expensive, and this is reflected in the VIX index.

Q: What is the VIX Index currently and how does this compare, say with early 2020?

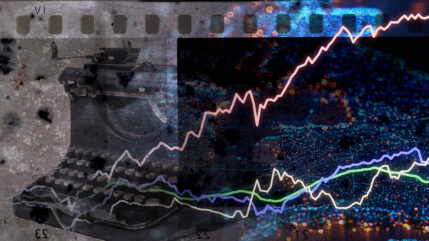

James: At the time of writing the VIX is at 33. Its average value over the last ten years is around 17, so the index is currently forecasting above average volatility in the US equity market for the time being. However, during the pandemic-induced crash in February/March 2020 the VIX reached levels exceeding 80, which is an indication of just how alarming that crash was.

The VIX Index over the last ten years (15/03/12-15/03/22)

Source: Bloomberg

Q: Are there any other similar Indexes for other stock markets?

James: FTSE Russell provides similar indices for the FTSE 100 index, based on expected 30 day, 60 day, 90 day, 180 day and 360 day volatility, although these only price once a day and not intra-day like the VIX. At the time of writing the 30-day index is sitting at 32, similar to the VIX, while it peaked at around 70 during the pandemic.

Q: Which stock market/Indexes are the most/least volatile?

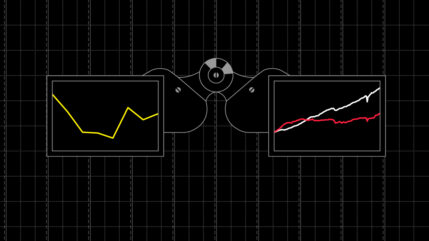

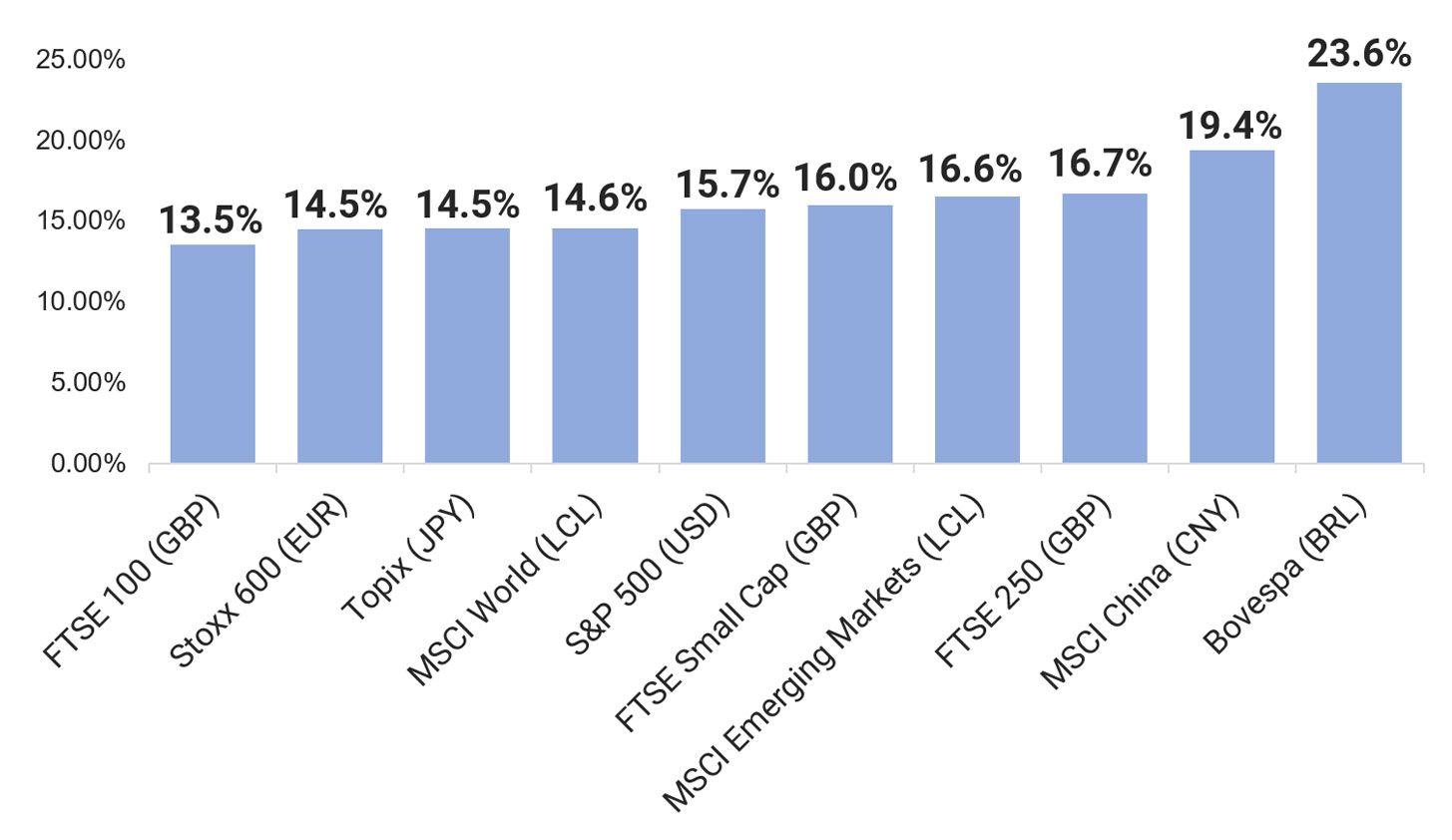

James: Broadly speaking, emerging market indices tend to be slightly more volatile than developed market indices. Also, medium and smaller companies typically experience more volatility than larger companies. The chart below shows the volatility of monthly returns over the last five years for several major equity indices, and the developed markets have similar levels of price movement while some emerging markets like China and Brazil have seen more volatility. Additionally, the FTSE 250 and FTSE Small Cap indices, which track medium and smaller companies, have been more volatile than the FTSE 100 index which measures large-cap shares.

Volatility of monthly returns over the last 5 years (28/02/17-28/02/22)

Volatility of major indices. Source: Bloomberg & Courtiers

Q: When referring to individual shares, what is volatility?

James: As I mentioned earlier, volatility is a measure of how much variation there is in the price of an asset. Shares which experience bigger swings in their day-to-day price can be considered more volatile than shares which see only modest movements. Information published by CMC Markets shows that Cineworld was the most volatile stock in the FTSE 250, with Restaurant Group ranked fourth.

Q: What causes one stock to be more volatile than another?

James: Many things can cause a stock to be more volatile. During the pandemic, shares in hospitality and travel companies were especially volatile as they were heavily impacted by lockdowns. In the last few weeks, stocks with exposure to Russia have seen spikes in volatility.

Q: Why does the volatility of individual shares matter?

James: It matters to an extent because high levels of volatility is something you generally want to avoid in a portfolio. However, a stock having a high volatility wouldn’t necessarily prohibit us from investing in it – that’s where diversification comes in. If the stock is part of a diversified portfolio then its individual volatility would have only a minimal impact on the overall portfolio.

Q: How is the volatility of an individual stock measured?

James: In general volatility is measured using a metric called standard deviation. Let’s say you have the daily returns of Amazon shares for a year. Loosely speaking, the standard deviation measures how much, on average, each daily return deviates from the average daily return. If Amazon has had a volatile year, then its standard deviation of returns for that year will be quite high.

Q: What stocks tend to be most/least volatile?

James: Broadly speaking, stocks which have a higher correlation with the strength of the economy tend to be slightly more volatile than those which don’t. For instance, when the economy entered recession during the global financial crisis, banking stocks were hit especially hard. However, every stock will have its own idiosyncratic risks which can cause its volatility to rise.

Q: What is the relationship between a share’s volatility and its dividend? Do investors in highly volatile shares expect higher compensation?

James: Very broadly speaking, a company that is able to pay strong, consistent dividends is typically less volatile as it is in good shape as a business. Paying dividends does however, have an effect on the company’s market value. If a stock is priced at £25 per share and it decides to pay a dividend of £1 per share, then all else equal, the share price will drop to £24 on the ex-dividend date. This affects the volatility of the price, but not the overall return to the investor as they still receive the £1 dividend and can reinvest it in the stock if they wish.

Q: I can see why share volatility might matter to a short-term investor, but what about long-term investors, why should volatility matter to them?

James: Volatility is much less relevant to a long-term investor, who has no urgent need to draw on their invested capital. If you’re invested in the stock market, then periods of high volatility, like the financial crisis in 2008 and the Covid crash in 2020, are inevitable. But markets eventually recover from these downturns, so the long-term investor learns to live with them.

Q: How does Courtiers monitor and manage volatility within its funds/individual stocks when high volatility makes protection against downside risk through the use of options too expensive?

James: The best protection you can give yourself is simply to diversify. In the Courtiers Total Return Funds, we use derivatives to obtain broad exposure to some of the major indices such as the FTSE 100 in the UK and the Stoxx 600 in Europe. Our broad US exposure is diversified further still with two indices instead of one – the S&P 500 index and the Russell 1000 Value index. In addition to this broad equity exposure, we have a portfolio of around 45 individual stocks, including some emerging market stocks, which allows us to look for value opportunities on an individual company basis as well as a regional basis. The two Courtiers Equity Funds, which are only allowed to invest in individual stocks, manage volatility by following an equal weighting policy. This ensures that the funds cannot become too concentrated in a couple of overweight stocks.