“There is only one kind of shock worse than the totally unexpected: the expected for which one has refused to prepare.”

Mary Renault – The Charioteer

You might think you know how much life insurance your employer provides as part of your employee benefits package. You may not be aware, however, that in the event of your death your next of kin could receive a lot less than they expect. This is owing to a bizarre piece of legislation that treats company life assurance schemes as pensions. To be forewarned is to be forearmed and there are ways to avoid the trap.

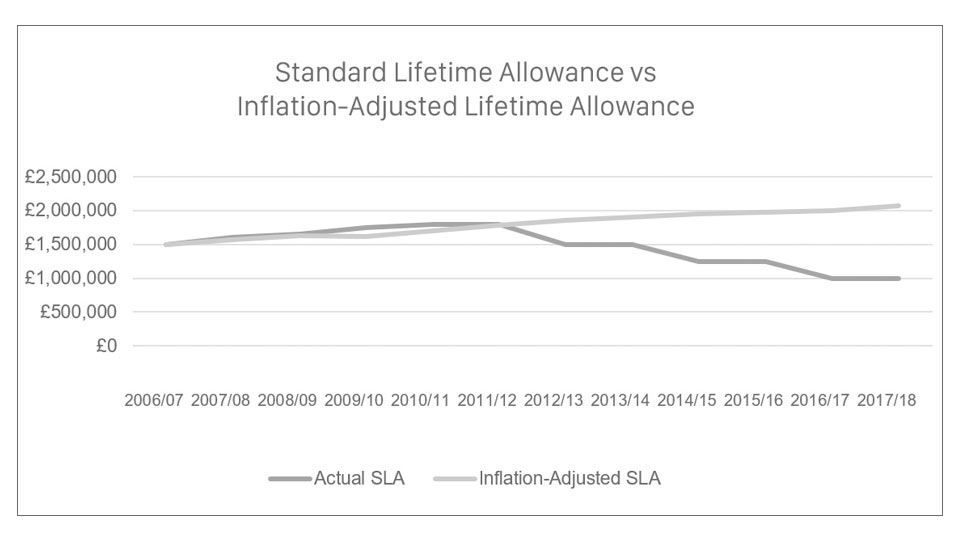

First, the briefest of history lessons. In 2006 Gordon Brown introduced the Lifetime Allowance as a way of kerbing excessive retirement saving by supposed ‘fat cats’. Those caught with pension funds over the new cap stood to lose 55% to HMRC. The Lifetime Allowance started at a relatively healthy £1.5 million and steadily increased to £1.8 million by 2010. In the years since, however, it has been inexorably eroded and now stands at just £1 million. Had it kept pace with inflation (as measured by the Retail Prices Index) it should now stand at more than £2 million:

You could argue that £1 million is still pretty generous and you’d have a point, especially since the average UK pensioner retires with a total private pension fund worth around £50,000, according to recent research by Aegon.

What most people don’t realise, however, is that it isn’t just your pension that gets assessed against the Lifetime Allowance. In the event of death before retirement, company death-in-service benefits are also usually included. Once you factor this into the equation, suddenly some very ordinary people start getting caught up in a tax charge originally targeted at the ultra-wealthy.

Example

Let’s assume you have built up a pension fund of £600,000 and earn a basic salary of £125,000. Your employer provides a death-in-service scheme paying out four times your basic salary on death. You have discussed things with your partner and together you understand that, in the event of your death, a lump sum payment of £1,100,000 will be made.

You then die unexpectedly. Your £600,000 pension is paid out to your partner as a tax-free lump sum but when it comes to your death-in-service, only £445,000 is paid. The remaining £55,000 disappears as a Lifetime Allowance tax charge because your total benefits exceeded the Lifetime Allowance by £100,000.

Figures obtained by Canada Life, a leading provider of employer death-in-service schemes, estimated that only 3,000 people were affected by the Lifetime Allowance in 2006 but by 2016 more than 300,000 were caught.

Some employers, including the BBC, have adopted a ridiculous solution to the problem – cap all pay-outs at £1 million. Returning to the previous example, had you worked for the BBC your widow would have only received £1 million rather than £1,045,000. This brings to mind Baldrick’s plan to solve the problem of his mother’s low ceiling by cutting off her head. Given the choice, surely we’d all prefer to have 45% of something than 100% of nothing?

A less hysterical solution is for employers to change the basis on which death-in-service schemes are established. Thousands of employers have already replaced traditional schemes with excepted life plans and we expect to see this trend increase exponentially. Excepted life plans sit outside pension legislation so are not tested against the Lifetime Allowance, they cost about the same as regular death-in-service plans and are not much more onerous to administer.

You might think, therefore, that every employer would replace traditional death-in-service plans with excepted life schemes but clearly this isn’t the case. We can attribute the lack of traction, in part, to a general lack of awareness but the other major barrier is fear that such schemes will be judged in future to be tax avoidance. The position for traditional death-in-service schemes is clear and well-tested in court. The position for excepted life schemes is quite the opposite – no case law yet exists and HMRC is unwilling to pass official judgement.

Regardless of any uncertainty surrounding the tax position of excepted life schemes, there’s a strong argument to say that it is better to use a vehicle which might be subject to tax reassessment in the future than to use one which definitely will result in a tax liability now.

Some companies will still decide it is better to limit benefits to £1 million than to risk future run-ins with HMRC. If that’s the case, they will need to start being creative about what other benefits they offer employees in place of pensions and life assurance. There are lots to choose from.

If you need advice or guidance with your company’s employee benefits, our Corporate Client Team can help.