Background

During the 2010s, and right through to the end of 2022, we were negative about the prospects for long-dated gilts. Their yields seemed paltry compared to returns from other investments and offered little margin of safety against a return of inflation, which lay dormant through most of that period.

Exhibit 1 – UK RPI inflation

Source: Bloomberg / Office for National Statistics (ONS)

The above chart shows the inflation averages pre the date when the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) of the Bank of England (BoE) assumed responsibility for interest rates in June 1997, and the average rate of RPI inflation post June 1997. The averages are 6.52% p.a. in the pre-independence period, and a much improved 3.44% p.a. subsequently (bear in mind I am using RPI as that was, historically, the benchmark for inflation and not CPI, which tends to run around 1% p.a. lower).

The UK’s central bank can’t take all the credit for the 21st century’s so far miraculous improvement in inflation because the trend was already under way in the late eighties.

1990 heralded the start of an extraordinary bull market for gilts with yields collapsing. Taking the 10-year benchmark gilt as an example, its yield dropped from 12.84% p.a. at the beginning of 1990 to just 0.08% p.a. in the Covid blighted Spring of 2020.

Exhibit 2 – UK 10-year gilt yields

Source: Bloomberg

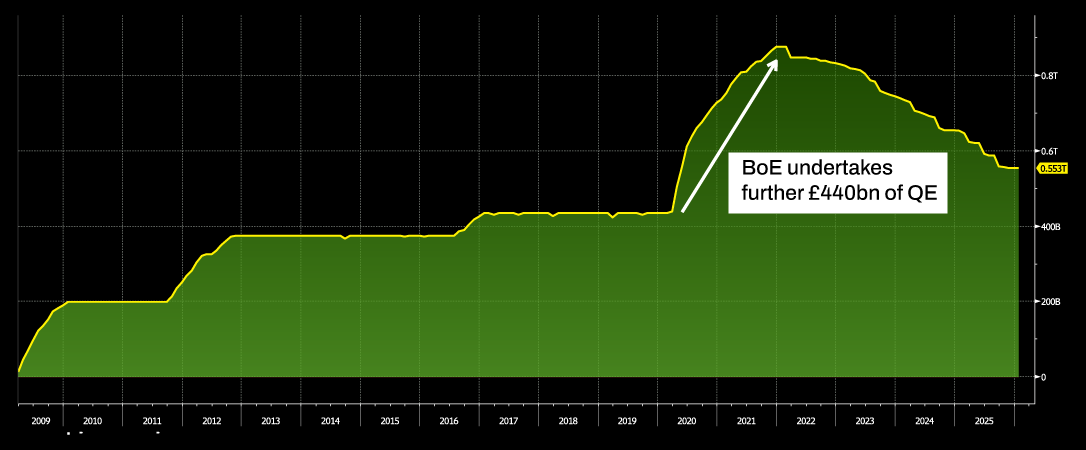

In 2019 yields looked like trending upwards, but Covid intervened the following year and the MPC responded with an aggressive round of QE, purchasing bonds to the tune of £440bn, more than doubling its stock of gilts (see Exhibit 3) and reducing the UK Base Rate to just 0.10%, its lowest ever.

Exhibit 3 – stock of UK government bonds (gilts) held by the Bank of England (BoE)

Source: Bloomberg / Bank of England (BoE)

The BoE’s Spring 2020 Covid-induced intervention gave gilts one final boost before their 30-year secular bull run came to a calamitous end. The 10-year yield hit a low of just 0.08% p.a. in that year and even the 20-year issue could muster a yield of just 0.51% p.a. at its nadir. This meant that gilt holders were betting on the BoE sustaining QE indefinitely with inflation, like the dinosaurs, being banished as a dim and distant memory of a bygone age.

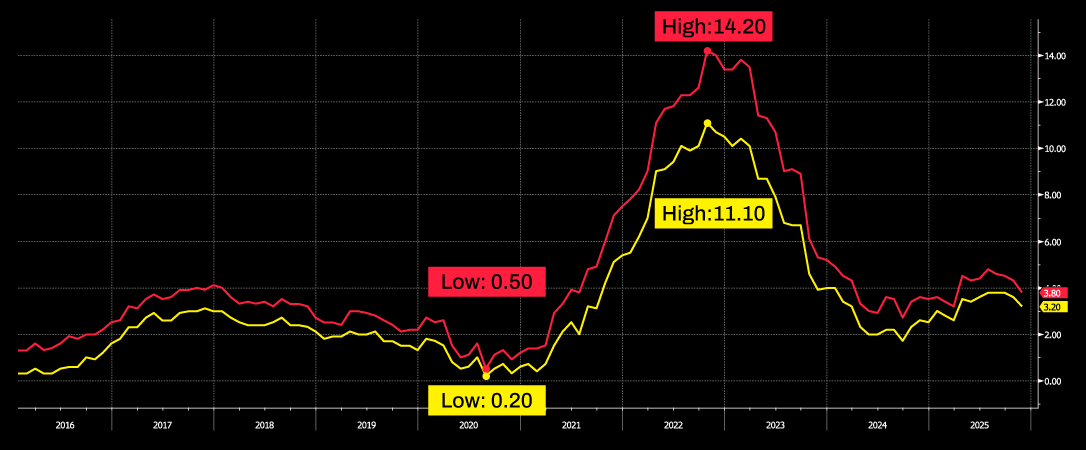

Unfortunately, the BoE’s intervention proved disastrous. With the economy shutting down voluntarily to slow the spread of the virus, families hoarded cash and most of the additional liquidity injected by the BoE was stored. When the pandemic eventually ended, demand was bolstered by enlarged savings, but supply could not respond fast enough, creating a massive spike in inflation (see Exhibit 4) to which the BoE responded with a series of rate hikes (see Exhibit 5).

Exhibit 4 – UK inflation % (RPI & CPI)

Source: Bloomberg / ONS

Exhibit 5 – UK base rate

Source: Bloomberg

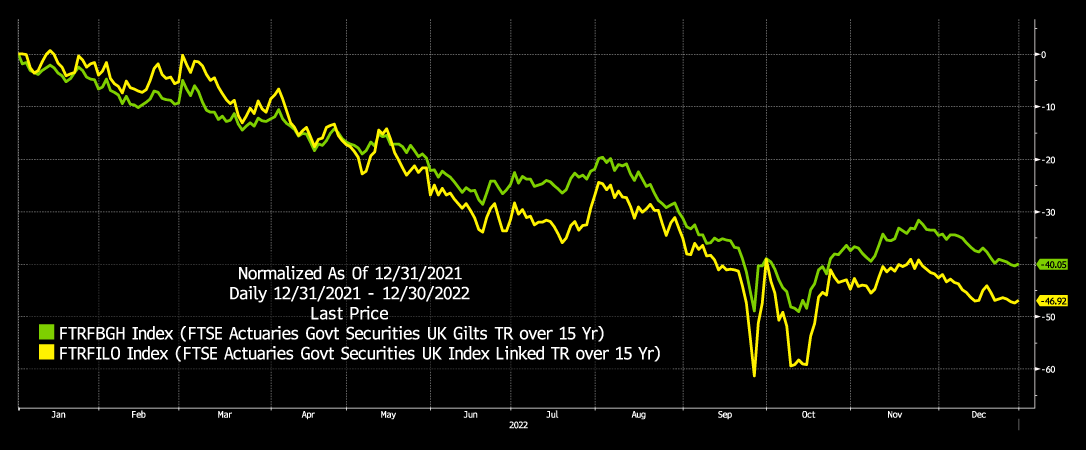

The spectre of high inflation and a rapidly rising UK base rate spooked gilt markets so much that in 2022, long-dated conventional gilts lost -40.05% (and that allows for income) but index-linked issues did even worse at -46.92% (see Exhibit 6).

Exhibit 6 – total return from conventional long-dated gilts (green) & index-linked long-dated gilts (yellow) in 2022

Source: Bloomberg

2022 showed that index-linked issues can perform just as badly, and worse, in an environment where inflation is rising. This may seem counter intuitive, but remember that yields from index-linked gilts are based on two factors:

- The expected long-term interest rate.

- The expected level of future inflation.

It follows that the notional yield from an index-linked issue will be 1) the expected long-term interest rate less 2) the expected level of future inflation. The difference between the yield from the conventional issue and the index-linked issue with the same term remaining is known as the “spread”. That spread is, de-facto, the market-expected future rate of inflation. Exhibit 7 looks at the yields from the 20-year conventional and index-linked issues from the beginning of 2000.

Exhibit 7 – 20-year conventional & index-linked gilt yields from the beginning of 2000

Source: Bloomberg

On 3rd December 2021, the nominal yield from 20-year index-linked gilts was -2.899%. At the same time, the yield from the conventional 20-year gilt was 0.94% with the spread, the expected future level of inflation, 3.84% p.a. (0.94% minus -2.899%). In other words, investors in conventional UK gilts were assuming that future inflation would average 3.84% p.a. but were accepting a fixed yield of just 0.94% p.a. over a 20-year period. Holders of the 20-year index-linked issue were accepting a negative notional yield of a staggering -2.899% p.a., thus guaranteeing a decrease in the future purchasing power of their capital – irrespective of the actual level of inflation. The reasons for this anomaly are twofold:

- The BoE’s post Covid QE of £440bn distorting the market.

- The UK’s defined benefit pension schemes’ obsession with LDI (Liability Driven Investments) creating an unnatural demand for long-dated gilts.

Gilt investors woke up to the horror of this situation in 2022 and experienced their worst annual return on record, and index-linked holders were not spared either.

Summary

Today’s market for gilts has normalised compared to 2022 and so the key decisions for any would-be buyer of long-dated UK government bonds are:

-

- Do I trust the future creditworthiness of the UK government?

- What is my future expected rate of UK inflation?

- Do I believe the BoE, and the government, will remain committed to fighting inflation?

The current market expected average UK inflation rate over 20 years is 3.01% p.a. In my view, this is high, especially as the method of calculating indexation of both yield and capital will shortly switch from RPI to CPIH. Even using historic RPI, which runs hotter than the CPI for technical reasons, the UK’s very long-term average rate of inflation spanning over 300 years is just 1.79% p.a.. Buyers of the latest 20-year index-linked issues are expecting inflation to run much higher than its historic average and way in excess of the BoE’s 2% p.a. target.

As 2022 shows, index-linked issues don’t necessarily behave as investors expect, and only protect savers’ money when the increase in the rate of inflation rises above expectations for prolonged periods – with no expectation of inflation being hammered back down by the BoE.

Conventional gilts now provide investors with a reasonable margin of safety over expected inflation. For example, the 20-year issue presently offers a fixed yield of 5.01% p.a., which is comfortably in excess of current annual RPI & CPI inflation at 3.80% and 3.20% respectively.

At these levels, I would not be a buyer of index-linked gilts.