Our central bank has thrown off its reputation as a stuffy old institution that keeps its facts and figures close to its chest, and its economic opinions even closer. The new style Bank of England now publishes articles under whizzy names like “The Dog and the Frisbee” and gives free access to its “millennium of macroeconomic data” which is intriguing to anyone nerdy enough to plot financial conditions back to Norman times, and I am nerdy enough to do just that!

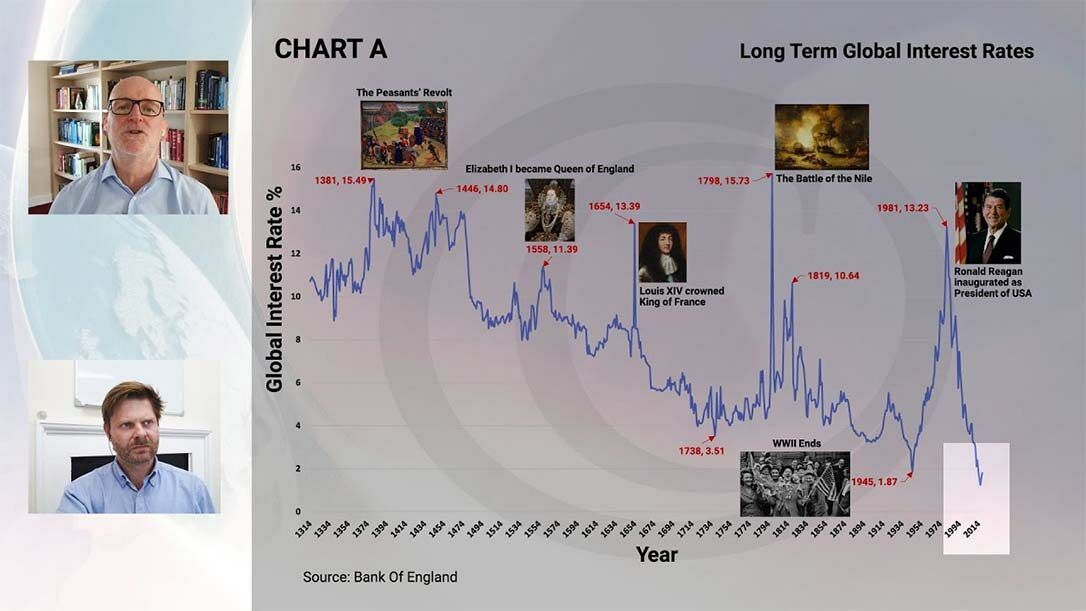

The latest Bank of England offering is compiled by Paul Schmelzing which tracks long-term global interest rates over the last 700 years.

CHART A – Long Term Global Interest Rates

Source: Bank of England.

The series opens in 1314, the year Robert the Bruce kicked Edward II’s backside at the Battle of Bannockburn, since when interest rates have been trending downwards to reach present record low levels.

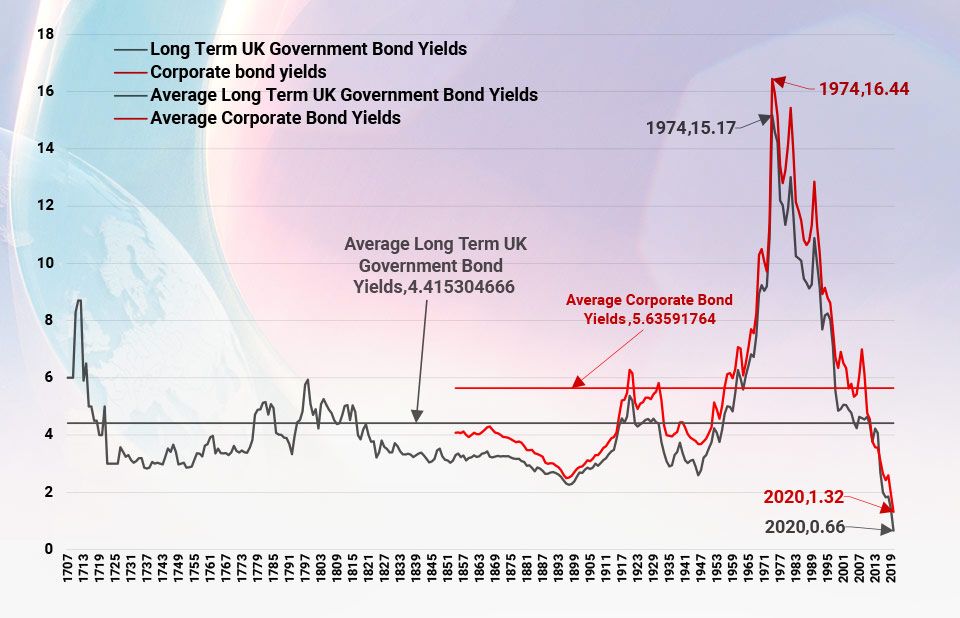

You will find similar depressed levels for UK government bond yields, as highlighted by Chart B below showing figures dating back to 1707.

CHART B – Long Term UK Bond Yields from 1707

Source: Bank of England, Bloomberg & Courtiers. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future returns.

Long term (30 year) UK government bond yields have bottomed at 0.66% this year whilst long term (15 year) corporate bond yields have hit a low of 1.32%.

A couple of months back I became irritated by commentators that opened their articles about Covid-19 with “these unprecedented times”. Covid-19 is not unprecedented because we have experienced many pandemics over the last few hundred years. However, interest rates at these levels are unprecedented and as someone who has lived through the record high rates of the 1970s, 30 year gilt yields at sub 1% just seems bonkers.

So what are the reasons for investors’ willingness to lend the British government money over 30 years at rates considerably lower than the current and long term rates of inflation? Nobody knows for certain, but it’s probably a combination of the following:

- A reduction in the volatility of changes to gross domestic product as we have become better at sustaining essentials, such as food and shelter.

- Interest rate decisions being moved from governments to central banks, thus taking away the ability of politicians to bribe voters by cutting lending costs.

- Globalisation making available a much larger work force at low labour rates.

- The increasing prominence of intangible products, like software, which can be sold to one person without denying another person access to the same product.

The list is not exhaustive and you can probably think of some more.

Whilst the above may explain the general downward trend in interest rates in recent years, they don’t really explain why the world, despite the best efforts of central banks, is creating money in vast quantities with no impact on inflation, seemingly debunking Milton Friedman’s mantra that “inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon”.

Believing central banks and governments have become so good at keeping price rises under control that 30 year gilts yielding 0.66% per annum is a good investment takes a colossal leap of faith. I am sceptical!

Bond prices seem to have hit the same dizzy and unsustainable heights that were reached by equities in late 1999, just before the bursting of the tech bubble. But a bust bond market could be much worse because holders of long term government securities regard their assets as “safe”. Anyone that lived through the 70s knows this to be errant nonsense. If the long bond yield returns to its 300-year average then holders of 30 years gilts will lose over 50% of their money. If they rise above their long-term average on a wave of inflation, caused by central bank money creation and government spending, the losses will be much worse. You have been warned!

Needless to say, we are not holding long dated bonds for Courtiers investors.