Europeans once referred to the UK as “the sick man of Europe”, and not without cause. Britain’s economy in the 1960s and 1970s was blighted by debilitating industrial relations, anaemic growth, high inflation, a falling pound and weak government finances that in 1976 sent Chancellor Dennis Healey cap in hand to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for a bail-out loan.

I know lots of Brits think our current situation is bad, and it could certainly be better, but it’s nowhere near as dire as it was in the 1970s. Today, our fellow Europeans have no cause to refer to Britain’s economy as “sick”, because theirs is in pretty bad shape too and has been for some time. German-led EU austerity has resulted in a lack of fiscal stimulus and poor job creation. Unemployment in the Eurozone is 6.2% (relatively good for the Eurozone where the long-term average unemployment rate is 9%) compared to 4.1% in the US and 4% in the “not so sick after all” UK.

German manufacturing has been the powerhouse of Europe’s economy for some time. However, its government’s fiscal policy legally restricting net annual borrowing to just 0.35% of GDP under the infamous “debt brake” has had catastrophic consequences for Germany, as well as its European and overseas partners. Germany runs a huge positive trade balance, which means it produces more than it consumes. Looked at another way, demand undershoots supply in Germany, so it exports surplus goods to countries where demand overshoots supply, like the US. Countries that run trade deficits provide the consumption to mop up the over-production for those countries that still believe in mercantilist policies that value trade surpluses over deficits. Mercantilism is a bit like cannibalism, long-discredited among thinking people but still practiced by pockets of the less enlightened.

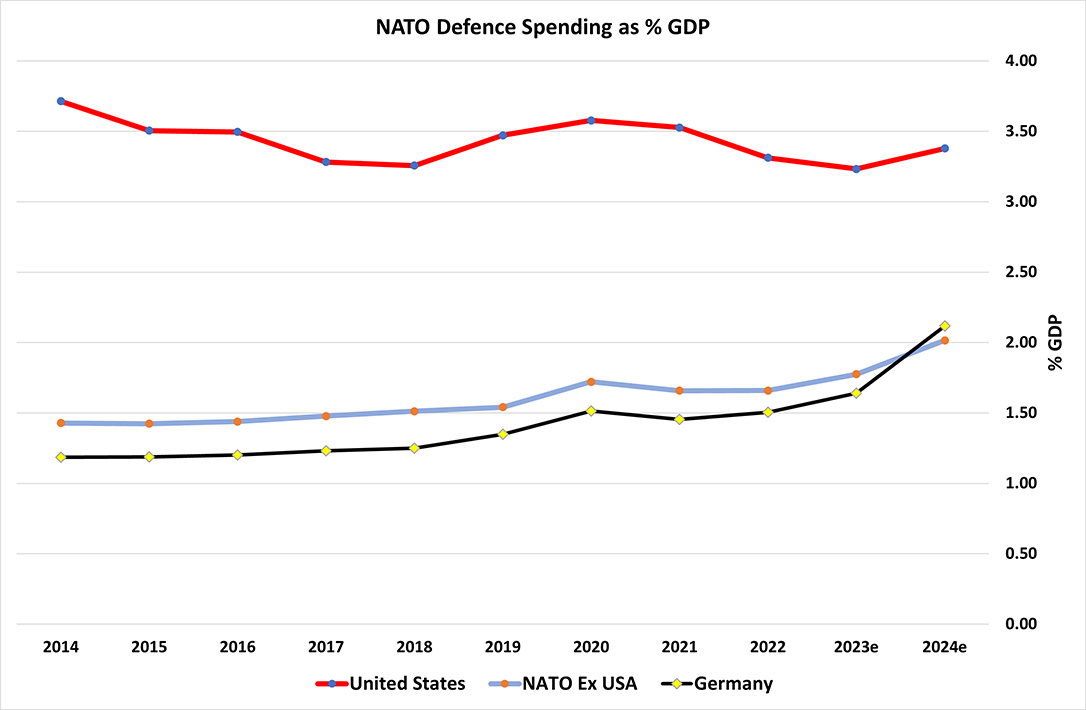

Requests to German politicians and officials for a change to their “beggar thy neighbour” economic and fiscal policies have fallen on deaf ears, but that is changing. Thanks to Putin’s war on Ukraine and Trump’s tariff wars, European policymakers are finally waking up to the fact that “fiscal prudence” has set them, economically, back 20 years compared to the USA. It’s also left them seriously exposed to invasion if America follows through on their threats to withdraw military support due to NATO members failing to spend the agreed 2% of GDP on defence. When you look at the numbers, it’s easy to sympathise with America running out of patience with Europe.

Chart 1 – NATO Members’ Defence Spending As % Of GDP

Source: NATO

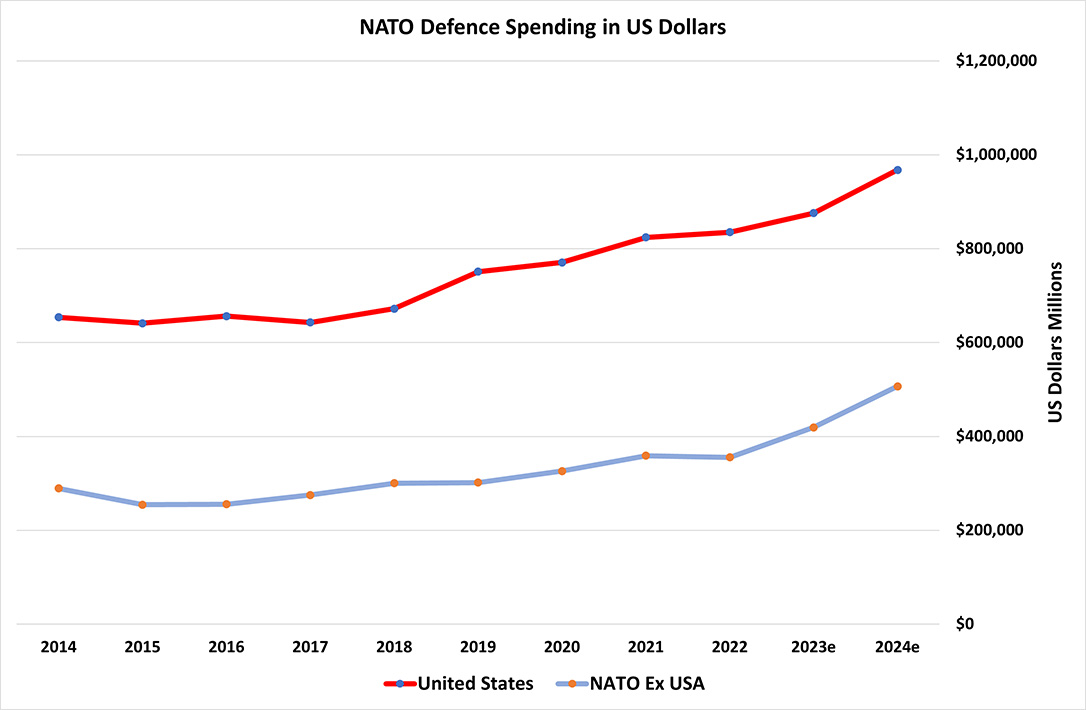

Chart 2 – NATO Members’ Defence Spending in US Dollars

Source: NATO

Charts 1 and 2 above show why many Americans have grown sick and tired of footing the bill for Europe’s defence. Not only does the US spend substantially more on defence than all its fellow NATO members put together (Chart 2), NATO members excluding the US barely muster 2% of GDP as a military budget whilst Americans spend over 3%. Whether you love Trump or not, when it comes to defence spending, he makes a valid point about Europeans freeloading whilst the USA foots the bill for their security. This is about to change.

On 19th March 2025, the EC (European Commission) published a White Paper on European Defence Readiness for 2030. Its opening sentences succinctly describe Europe’s plight as follows:

“Europe faces an acute and growing threat. The only way we can ensure peace is to have the readiness to deter those that would do us harm”

On page 2 the commission gets even more emphatic and says, “The moment has come for Europe to re-arm”. Strong stuff! (Anyone wanting to read the White Paper can access it here: Introducing the White Paper for European Defence and the ReArm Europe Plan- Readiness 2030 – European Commission)

Page 12 of the White Paper makes a chilling but accurate observation about the war in Ukraine:

“Ukraine is today using its experience from the frontline to continuously adapt and upgrade equipment to the point that Ukraine has become the world’s leading defence and technology innovation laboratory. Closer cooperation between the Ukrainian and European defence industries will enable first-hand knowledge transfer on how to best use innovation to achieve military superiority on the battlefield, including on rapidly scaling up production and updating existing capabilities”

It’s chilling to think that a conflict that has killed hundreds of thousands of people is seen by the EC as a “…defence and technology innovation laboratory”, but it does show that the bureaucrats in Brussels are at last taking the security of the continent seriously and gearing up to massively expand their member countries’ defences. But there is a lot to do, including altering the whole thinking around investment in defence, which has been disincentivised on the grounds of ethics, or outright prohibited by some intergovernmental bodies. For example, the European Investment Bank (EIB) specifically names ammunitions and weapons production as activities that cannot benefit from EIB financing.

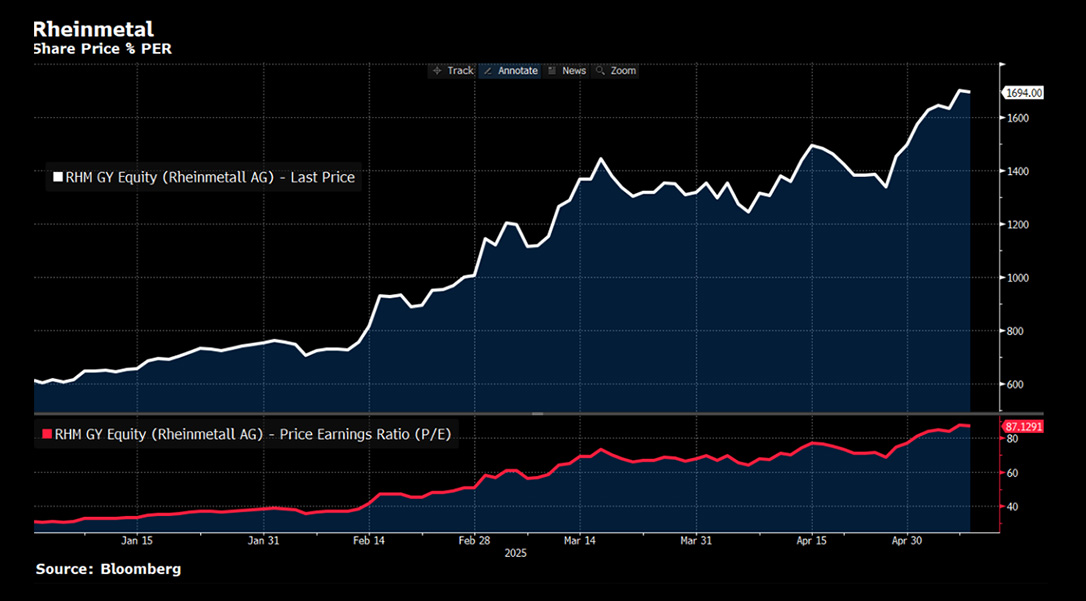

Aside from reversing Europe’s shift to passivism, there is a more immediate practical problem for the EU – its defence industry is tiny, accounting for roughly 0.5% of GDP. That’s around one third of the size of America’s. This makes European defence companies attractive, at least in the short term. Germany’s Rheinmetall has seen its share price soar by over 175% so far this year and it now trades at 87 times earnings (net profits) making it even more expensive than Tesla.

Source: Bloomberg

Some European countries have much larger defence sectors than others, which includes Britain, something the EC is aware of and it specifically singles out the UK as “…an essential European ally with which cooperation on security and defence should be enhanced in mutual interest, starting with a potential Security and Defence partnership”. The need for Europe to unite around common defence objectives could provide the UK with the opportunity to reset its post-Brexit trading arrangements with the EU and give a boost to our manufacturers.

What does all this mean for investors?

A simplistic way to try and benefit from the rearming of Europe would be to buy defence companies, like Rheinmetall, but these have become very expensive. I’ve mentioned for some time that European stocks are relatively cheap compared to the US, mainly because they have not increased earnings as fast as their American counterparts. This is due largely to the fact that German-led EU austerity caused Europe’s economy to stagnate. But Germany can no longer sit back and do nothing as Russia threatens its security, China threatens its manufacturing supremacy and Trump’s tariffs threatens its export-led economy. Turning even a fraction of its considerable manufacturing capacity towards the production of ammunition and weapons will help boost German, and European GDP considerably.

Perhaps this is the moment when the sleeping giant of Europe awakens. If that is the case, then European stocks could enjoy a period of prolonged outperformance compared to the US.