In the Spring of 1981, 364 economists signed a statement severely criticizing the economic policies of the then Conservative government led by Margaret Thatcher. They said, “present policies will deepen the depression, erode the industrial base of our economy and threaten its social and political stability”. At the time, the UK had just experienced five successive quarters of negative growth – a proper recession! Those economists were wrong. Q2 of 1981 saw growth return and the 80s became a boom period for the UK.

There is a funny story about Michael Foot, then leader of the opposition, questioning Margaret Thatcher about the letter signed by those 364 eminent economists and asking her to name two economists that agreed with her. “Alan Walters and Patrick Minford” she replied, after which one of her advisors said, “Thank goodness they didn’t ask you for three Prime Minister.” Alan Walters died in 2009 but Patrick Minford is still going strong at 79. Some of you will remember him as the Brexiteers’ economic champion who in 2016 stood against the majority of economists that were queuing up to say that Brexit would be a disaster (the jury is still out on that!). Professor Minford clearly loves an underdog because he is just about the only economist saying anything positive about the Truss and Kwarteng budget.

Fiscal probity has been the cornerstone of UK government policy since 2010, but it has yielded little in economic growth and productivity improvements have been pitiful. Inequality in that time has widened because the counterbalance to fiscal austerity is loose monetary policy (lower and still lower interest rates) which have pushed up asset prices and benefited those with wealth.

You have got to give the Prime Minister and her Chancellor credit for trying something different. There are similarities between Thatcher’s policies in 1981 and the policies of today. The present community of leading economists has responded to the September 2022 budget in the same negative way that their predecessors did in 1981. I guess if you are going to have a solitary economist standing in your corner then Patrick Minford is the one you would want. But is he right to back this government’s policies and just how bad are the UK’s finances?

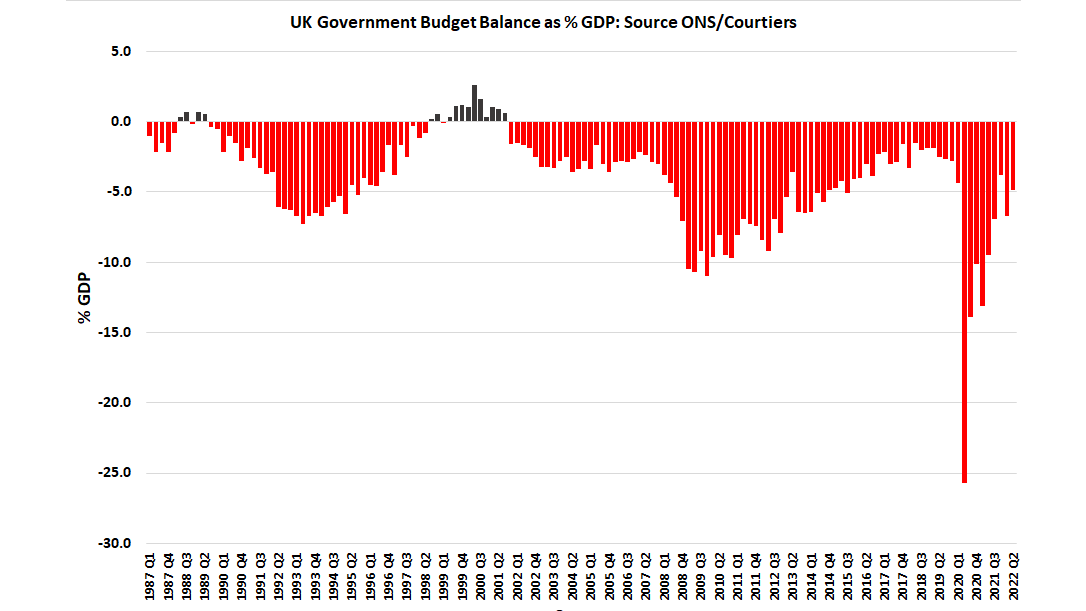

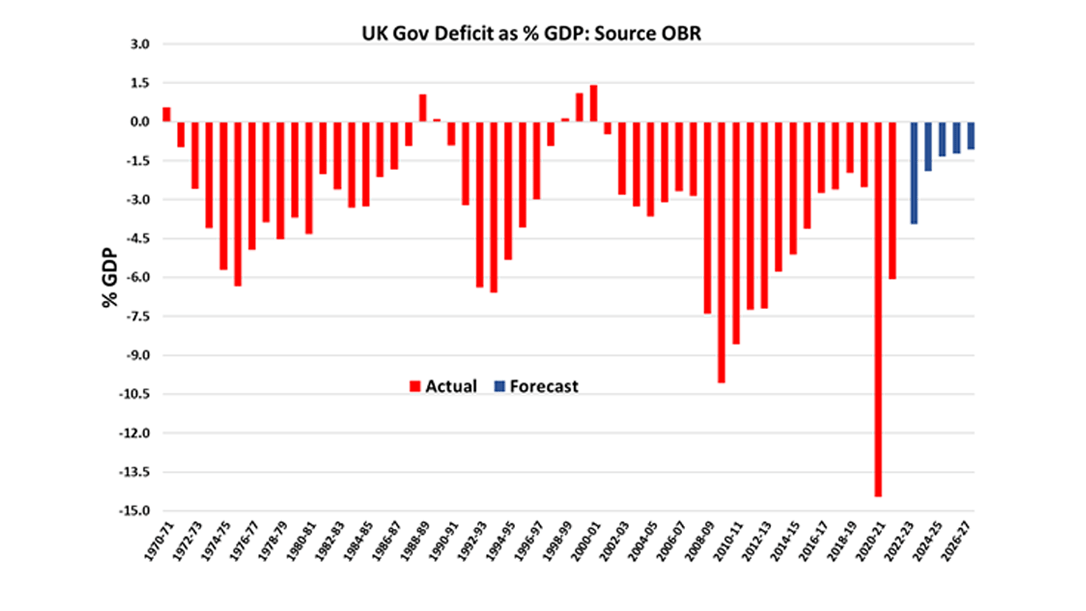

The UK’s budget deficit exploded in 2020 when the then Chancellor, Rishi Sunak, supported families and businesses through the pandemic.

Chart A

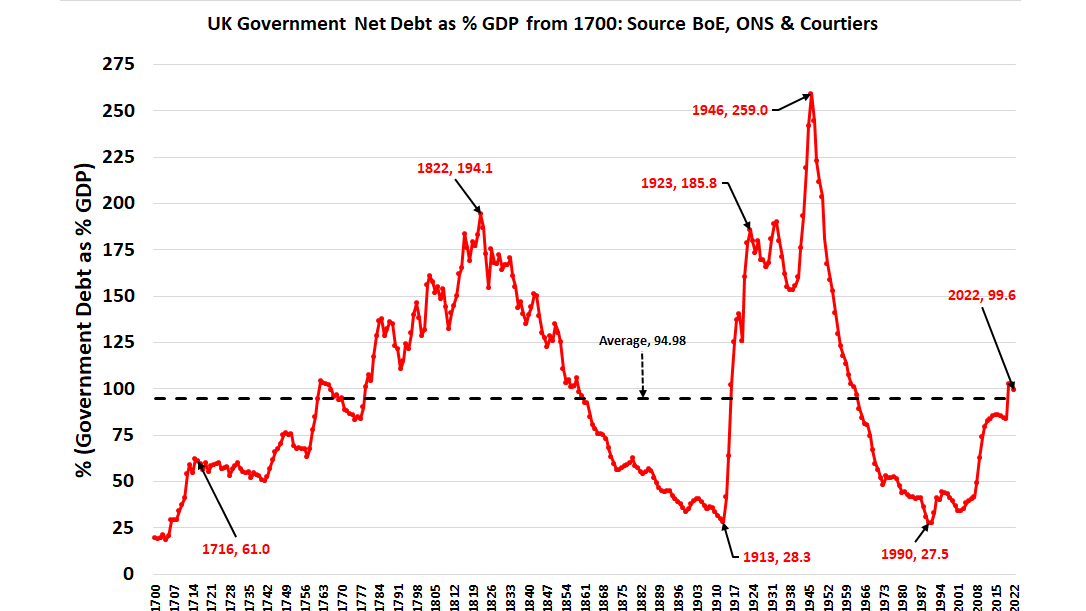

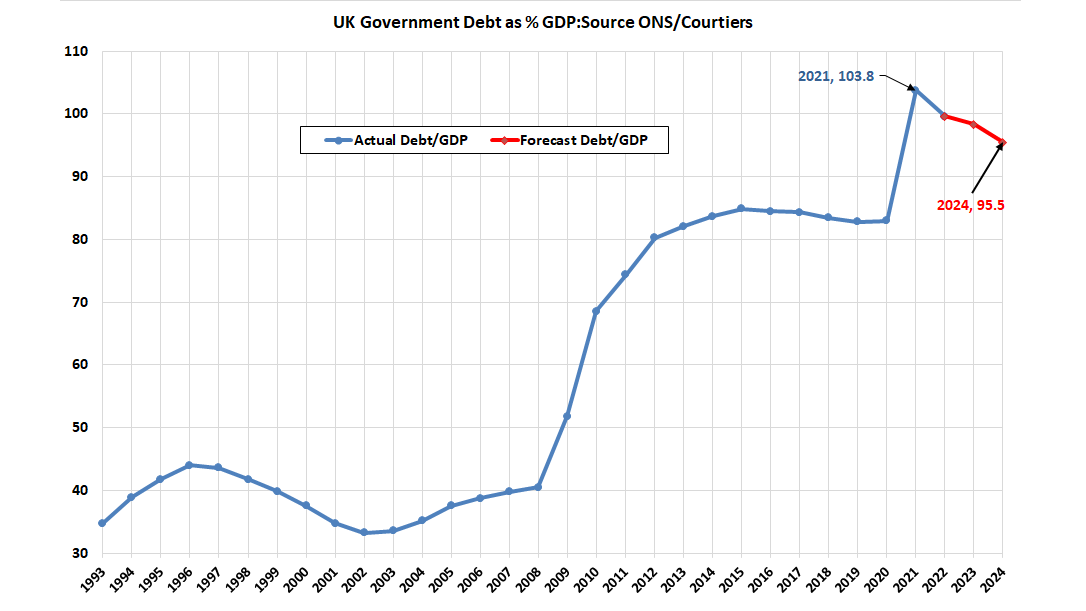

The rolling 4 quarter deficit peaked at -25.7% of GDP in 2020. It is presently -4.9% which is still high, but a big improvement on 2020/2021. As a result of running a deficit, government net debt has risen to 99.6% of GDP. High as that may seem, it has only just climbed above the long term average of 94.98% and is way below the post-World War II record of 259%.

Chart B

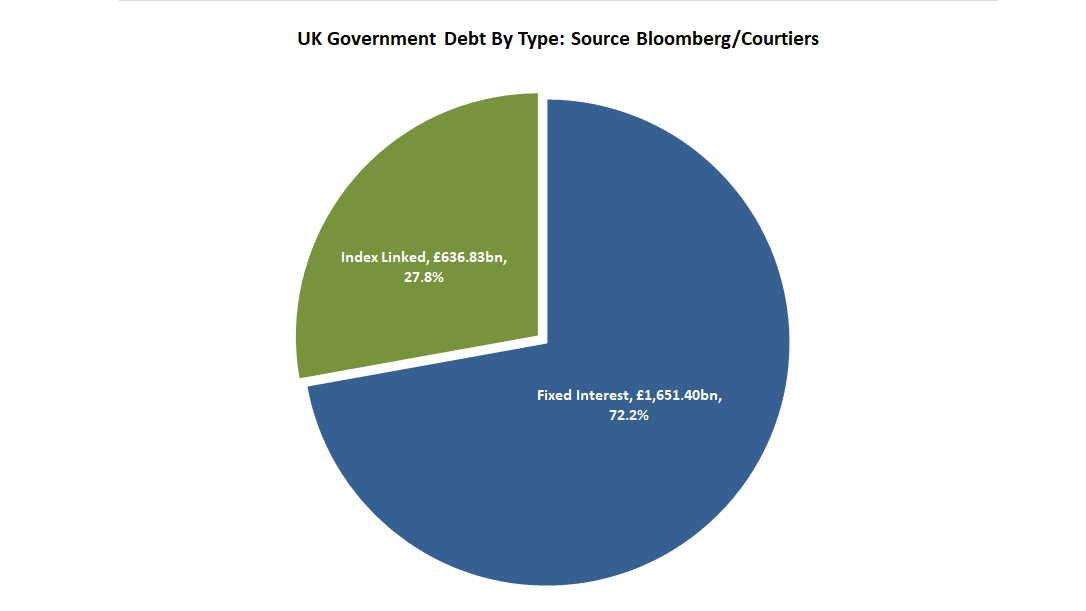

Critics say Truss and Kwarteng’s policies will push up the value of government debt because much of UK borrowing is inflation linked. This isn’t true, 27.8% of UK borrowing is linked to inflation, the rest is on fixed interest.

Chart C

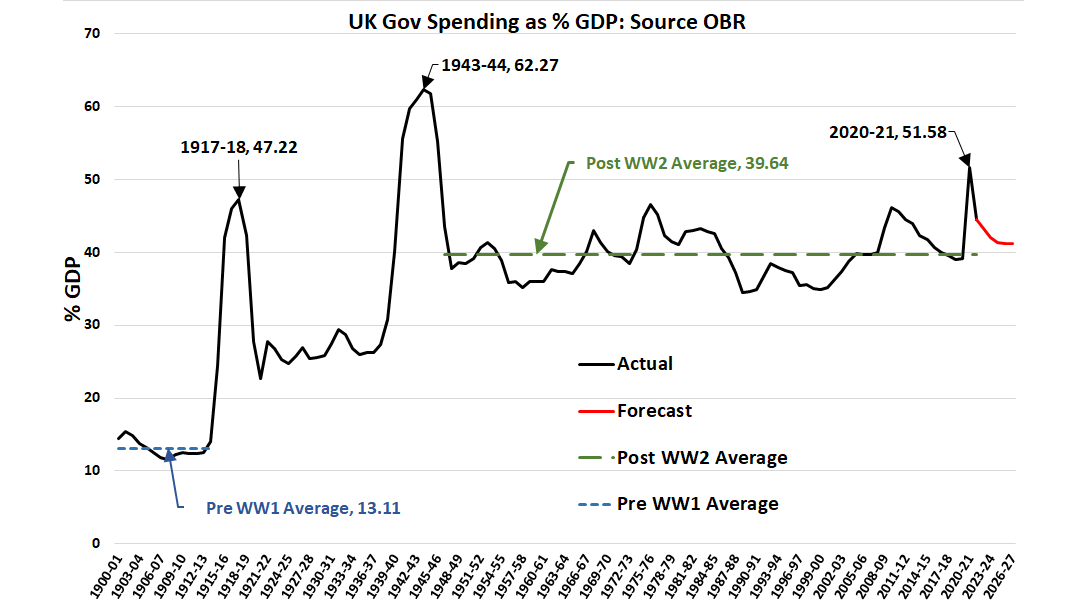

Truss and Kwarteng have given notice that they want government spending to be cut back. There is a lot of scope for this. Chart D shows UK government spending year by year as a percentage of GDP. The State is now much more involved in our economy than at anytime since World War II.

Chart D

The OBR (Office for Budget Responsibility), which was established to give an independent assessment of the effects of fiscal policy, has not yet costed Kwarteng’s tax cuts. That means we are still working on deficit forecasts from the spring. These are shown in Chart E.

Chart E

The UK government deficit has shrunk significantly since 2020/2021 and now sits at just 5% of GDP. Earlier this year the OBR forecast that it would drop steadily for the next five years (the blue bars in the above chart). Critical economists argue that this forecast is now way out as a result of the Kwarteng budget, but just how “way out” is it?

Writing for the Telegraph at the end of last month, Kwarteng said “the Medium-Term Fiscal Plan will set out a credible plan to get debt falling as a share of GDP in the medium-term”. That may seem odd when the OBR has predicted that the UK government will run a deficit for each of the next five years even before the Chancellor’s latest tax giveaways. But the debt to GDP ratio can fall even when the Government is running a deficit, provided the ratio of the deficit to nominal growth is lower than the ratio of total debt to total GDP. With high inflation, that’s not difficult to achieve. Ronald Reagan described inflation as “….violent as a mugger, as frightening as an armed robber and as deadly as a hitman.” Nobel prize winning economist Milton Friedman referred to inflation as “…taxation without legislation”. Both had experienced the high price rises of the 70s and both knew that inflation is a stealth tax.

I did some “back of an envelope” calculations to project just how bad the UK finances may look by the end of 2024 assuming: –

- That the government runs a deficit of 5% of GDP for the next two years (the OBR were predicting deficits of just 1.91% and 1.34% back in the spring).

- That inflation continues at 8% per annum.

- That economic growth is just 1% per annum.

Even after assuming that the government’s annual deficit is over 3% of GDP higher than predicted by the OBR earlier this year and economic growth is a paltry 1% per annum, the debt to GDP ratio drops from 103.8% to 95.5% in just three years. That is because high inflation increases the nominal value of GDP at a faster rate than the increase in total debt.

Chart F

Perhaps the current cohort of economists are just too young to have experienced inflation, or perhaps, like the 364 that signed up to an erroneous statement in 1981, the herd is just wrong. Perhaps it takes an economist to have actually lived through the high inflation 70s (at 79 Patrick Minford fits that bill) to understand what’s going on, or a younger person with a brilliant mind and an acute understanding of the past, such as a University Challenge winner with a first-class degree in classics and history from Cambridge, a PHD in economic history and first hand experience working for leading international financial institutions. That describes Mr Kwarteng.

Experts have been queueing up to criticise the fiscal policies of this new government and predict Armageddon for the pound, gilts and UK shares. Forecasts for the demise of our currency, bonds and companies are greatly exaggerated. Our debt to GDP ratio is sustainable and only just above its long term average, our currency is cheap and there are lots of business opportunities in the UK which is well placed to be self-sufficient in energy, most of it renewable, over the next decade. And we can still compete with the world’s best, as we proved through the collaboration of AstraZeneca and Oxford University in being first out of the blocks with a vaccine. Investors write off the UK at their peril.