You don’t have to be an economist to realise that our economy is stalling, and pretty dramatically. I suspect economic output in the first half of this year will be down by -10% to -15%, and as far as recessions go, that’s huge.

The “stalling” is self-induced, so the questions being asked up and down our country, and throughout all other countries that have followed similar lockdowns, are:-

- Is the lock-down worth it?…. and

- Can we fire-up the economy when the restrictions are released?

The answers are “yes” and “yes”.

1. Is the lock-down worth it?

The coronavirus is highly contagious. It transfers easily between humans and rapidly infects large numbers of the population. It’s not possible to accurately assess the cost of UK social distancing and lock-down (collectively known as “NPIs”; non-pharmaceutical interventions) versus a more “laissez-faire” (let Covid-19 do its worst) approach (although many economists are excited by the prospects of comparing economic neighbours Norway and Sweden as the governments of these countries have taken different approaches, Sweden having opted for a more “laissez-faire” strategy). But although we can’t know the exact opportunity cost of using NPIs we can make a reasonable guess.

The coronavirus is highly contagious. It transmits easily from one human to another. Whilst the vast majority of people appear to recover as though they have had mild flu, (the Health Minister, Matt Hancock, being one of them) in some it develops into pneumonia which, without the intervention of a respirator and oxygen, will kill them.

We can be reasonably certain, therefore, that due to the virulent nature of this pandemic, a “laissez-faire” approach would have seen Covid-19 spread rapidly through the country. In fact the coronavirus transfers so easily that it is feasible that within a fairly short period of time 80% of Britons may have contracted it. Rough estimates seem to indicate that around 1 in 20 people that catch the disease develop secondary respiratory problems which, if untreated, prove fatal. So if 80% of the British population contracted Covid-19, and one in twenty of those 80% needed hospitalisation but couldn’t get it because the NHS was overwhelmed, the death toll could be north of 2.5 million. That is the equivalent of wiping out the entire population of Birmingham, Britain’s second biggest city.

“Laissez-faire” has an economic cost because the loss of so many people would:-

- Reduce the supply or goods and services through a fall in the workforce

- Reduce demand through a fall in the population

- Reduce economic activity because of fear (people would very soon stop going out to restaurants and socialising once their friends and relatives started dying)

- Cause businesses, seeing a drop in demand, to lay-off employees permanently

- Cause businesses, seeing a deterioration in economic conditions, to cut investment

In a paper published earlier last month Sergio Correia, Stephan Luck and Emil Verner looked at the effect of the 1918 Spanish Flu virus on America’s big cities, which had adopted different approaches to the pandemic spanning from “laissez-faire” to aggressive use of NPIs.1The cities that implemented NPIs did much better than those that didn’t. A one standard deviation increase in the speed of the NPIs (8 days) increased subsequent output by 5%. A one standard deviation increase in the period of the NPIs (46 days) increased output by approximately by 7%.

Earlier research on the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic published by Elizabeth Brainerd and Mark Siegler in June 20022 seems to contradict the case for NPIs as the authors noted that one more death per thousand resulted in an average annual increase in the rate of economic growth over the next 10 years of at least 0.2% per annum. On the face of it, this would support a more “laissez-faire” approach to the management of the coronavirus pandemic, but Brainerd and Siegler clarify this finding by stating that the number of flu deaths in 1918 and 1919 were a significant predictor of business failures in 1919 and 1920. The positive relationship between flu deaths and economic growth in the 10 years post the pandemic is because the cities and regions that suffered the higher mortality rate also suffered the biggest decline in economic output. In other words, the worse affected regions grew slightly faster than the others because they were recovering from a much lower base. This extra growth was not a change in trend, it was a return to the pre-Spanish Flu pandemic levels of GDP following a major loss of economic capacity.

History supports the use of NPIs which is, I’m sure, a key reason for the UK government putting our economy in lock-down.

2. Can we fire-up the economy when the restrictions are released?

Brainerd’s and Siegler’s paper showed that even those regions of the US that had been badly affected by Spanish Flu recovered quite well in subsequent years.

It is also logical to expect productivity to improve post-Covid-19, although one of the reasons, called “capital deepening”, is a little macabre (economics is not called the “dismal science” for nothing). A virus kills people and therefore reduces the size of the population, but it doesn’t destroy capital (unlike wars). Therefore, post-Covid-19, the amount of capital per head of the UK population will rise (that’s “capital deepening”), which will lead to an automatic improvement in productivity.

A less ghoulish reason for optimism is that human beings tend to be creative at overcoming their problems (it’s at least one of the reasons that Homo sapiens have become the dominant species on our planet). We may all be getting more than a little bored with a policy of social distancing that keeps us sitting at home, but that boredom can stimulate a burst of innovation. The German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche reckoned that boredom was an essential progenitor to creativity. In his 1882 book “Die fröhliche Wissenschaft” Nietzsche claimed that for the inventive spirits “boredom is the unpleasant calm of the soul which proceeds the happy voyage and the dancing breezes” He also claimed that the creative person must “endure [boredom]” and must “await the effect [boredom] has on [them]“. 3

In her 2016 book “The Science of Boredom” psychologist Dr Sandi Mann makes a similar case to Nietzsche arguing that boredom, like any other human emotion, is present for our long-term benefit and frequently shows as a precursor to creativity.

I’ve been quite amazed at the resourcefulness shown by businesses and people through the initial stages of the UK’s lockdown. We have a huge advantage compared to our ancestors that endured lock-downs in previous pandemics because we have social media, personal computers and the ability to work remotely. Lessons that companies and people learn from these experiences are likely to lead to improved ways of working when the lockdown ends. Many of us will also have developed new skills, and I speak from personal experience. Over the last 2 weeks I’ve become quite adept at using my mobile devices for video conferencing (which I hated until recently), which has become almost as natural to me as chatting face-to-face. I’ve even learned how to setup a YouTube account, with my own channel, and post videos to it. Old dogs can learn new tricks… if forced to!

Part of the economy will be put into mothballs, and unemployment will rise, but I don’t expect the UK to suffer much economic hysteresis, and the supply-side of the economy will bounce back strongly when this is all over.

As for demand, have you ever seen cows released into a spring field for the first time having been locked up over the winter? They leap and run around revelling in their newfound freedom and I dare say we will do the human equivalent post-Covid-19 and spend, spend, spend! Remember, the “Roaring Twenties” followed the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic (although I accept they didn’t end too well with the 1929 Wall St Crash!).

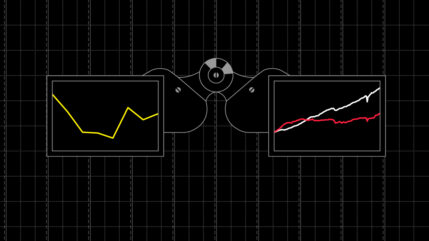

Stock markets have historically been pretty good at discounting the long-term future. Security values improved recently, although there will still be heightened daily volatility and large swings in prices until this is all over. Mankind has overcome past pandemics, and we will overcome this one. Evidence suggests that if we can minimise the short-term economic effect of Covid-19 we will reduce the deterioration in our output capabilities, which will be eventually improved through the lessons we have learned in the shutdown. Every cloud….!