“….in the November Inflation Report, the projections for inflation were the highest ever published by the Bank, while the forecasts for output growth were the lowest ever published.”

(Andy Haldane, Chief Economist of the Bank of England, 2nd December 2016)

The calm before the coming inflation storm has spanned 25 years. It has created an unprecedented bull market in government and high grade corporate bonds, which are now breathtakingly over-priced.

The first 18 years of this bond bull market were the result of increasing productivity in developed markets, fast capacity growth in emerging markets and a glut of world savings pushing up the price of safe haven securities, such as gilts (securities issued by the UK government). Post the 2008 global financial crisis, central bank QE (quantitative easing), which involves buying-up government debt, switched on the turbos and rocketed bond prices into the stratosphere.

The Bank of England’s objective with QE is to hold down interest rates and encourage borrowing at normal levels so that the money supply doesn’t collapse (as it did in America after the 1929 Wall Street crash with disastrous consequences). As there was no major depression after the 2008 crisis, most economists argue that QE worked.

I agree, but monetary policy can only alleviate the pain of a struggling economy for a short period, and the way in which QE works has unfortunate side-effects. One of these is that lower interest rates increase the value of existing assets. That is good news for the wealthy, but not good news for the less well-off, particularly if they are in low paid jobs, and especially if lower interest rates do not promote investment in the economy.

The economic recovery of the last 8 years has been shallow with virtually no improvement in productivity because businesses are just not investing in new capacity. Instead, companies have been taking on more employees, probably because they can sack workers if demand diminishes, whereas newly purchased machines simply stand dormant. This has been good for the bottom-line rate of UK unemployment, which is down to 4.8%, but as lots of the new jobs have been lower paid, productivity growth has been non-existent for nearly 9 years.

It gets worse. The average UK working household has seen a deterioration in net disposable income over the last 10 years. During the same period, their retired parents have seen an increase. Young working families don’t do any better when it comes to their net wealth. The under 45s have seen savings dwindle whilst their parents have seen theirs rise.

This explains why the country, given the opportunity to vote for change in the June EU referendum, did so. Which brings me around nicely to my main point, which is that vast numbers of voters in western democracies are unhappy with their lot. They used the power of the ballot box to kick out David Cameron in June, dash Hillary Clinton’s dreams in November and send Italy’s young prime minister, Matteo Renzi, to a humiliating defeat in December.

On 2nd December, Andy Haldane, Chief Economist of the Bank of England, said “….in the November Inflation Report, the projections for inflation were the highest ever published by the Bank, while the forecasts for output growth were the lowest ever published”. Central banks may be able to hold base rates low for a little longer, but the market will discount future increases, pushing down the value of longer-term bonds. Some predict an orderly correction to the bond bubble, but there is rarely such a thing in financial markets, which means a collapse of bond prices is a real possibility. This is why, as we move into the New Year, we have already slashed our allocation to long-dated bonds.

2016 was, on the whole, a very good year for COURTIERS investors. We managed to navigate the political problems well and our strong position in US dollars helped enormously. 2017 will be trickier. We have already cut our risk to long-dated bonds and, as always, we will be on the look-out for other risks whilst seeking to deliver reasonable returns. I would like to finish by thanking everyone that entrusted us with the care of their assets over the last year. We are very grateful for your confidence. I wish all our readers a very merry Christmas and a prosperous and peaceful New Year.

The change in mood will not be lost on our politicians. Theresa May promised that her government will now work tirelessly to support the “JAMs” (Just About Managing Families). You can expect similar language and promises from France’s Republican presidential candidate, Françoise Fillon, as he seeks to stop Marine Le Pen from taking power. Angela Merkel, having announced that she will stand for a fourth term, and having already refreshed Germany’s dwindling workforce by admitting one million young ambitious refugees, is now changing her language to recapture the ten percentage points of popularity that she lost as a result of her unpopular stance on immigration.

Monetary policy may have avoided a catastrophic collapse of the money supply, but it hasn’t created increases in standards of living for average working families. The only course now open to governments, which comprise politicians wanting to get re-elected, is to revert to fiscal policy, ie., public sector spending to boost demand. This is why there has been a lot of talk, both sides of the Atlantic, of investing in infrastructure. But can we afford it?

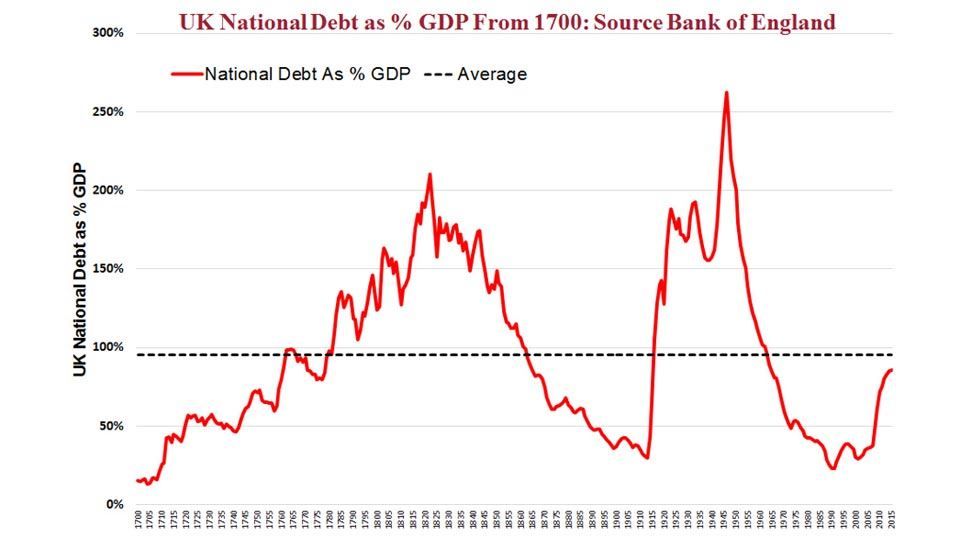

At the end of 2015, UK government debt was around 86% of GDP (see chart below). This may seem high, especially as it has shot up from the low levels reached in the mid-80s (in March 2008 UK government debt to GDP was just 35%). You may find it surprising to learn that in the UK this is still lower than the average rate of debt over the last 315 years, which is 95% of GDP. There is scope for governments to increase borrowing. Long-term interest rates are still very low (which makes the debt comfortably serviceable, at least in the short-term) and politicians won’t get re-elected unless they make working class people better off. It is for these reasons that western governments will return to more aggressive fiscal policies. When they do, the public sector will start employing more resources, boost demand and promote an upward movement in prices. That is good old fashioned demand-pull inflation, and it’s just around the corner.