Foreword from Gary Reynolds, CIO:

I have written about the perils of inflation for as long as I can remember. I experienced it first hand in the 1970s and watched monetarism bring it under control in the 1980s.

I have written about the perils of inflation for as long as I can remember. I experienced it first hand in the 1970s and watched monetarism bring it under control in the 1980s.

Things are changing. Monetarism has failed to create meaningful growth post the Global Financial Crisis and governments during 2020 have seen the benefits of fiscal intervention through the financial support they have provided to combat the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic. This has made the ministers that have introduced such measures very popular, something that will not be lost on politicians and which will encourage them to keep the financial support flowing.

Inflation is disastrous for holders of long dated fixed interest bonds (see my article of 6th November) and bad for the economy. I was going to write about the perils of inflation but then I remembered that one of our Analysts, Nyasha Jonhera, who joined us in January this year, studied and qualified in Zimbabwe during its recent period of rampant hyperinflation, one of the worst in history. Her experience, described below, is fascinating and should be a warning to all investors that whilst some inflation is better than deflation, too much is utterly devastating.

Zimbabwe became a nation of trillionaires when the country experienced hyperinflation, not because of fortune, but because one had to be a ‘trillionaire’ to be able to buy a loaf of bread and a pint of milk.

In the early ‘90s, prior to the inflationary period, the economy was pretty stable. The largest denomination in circulation was the Z$20 note.

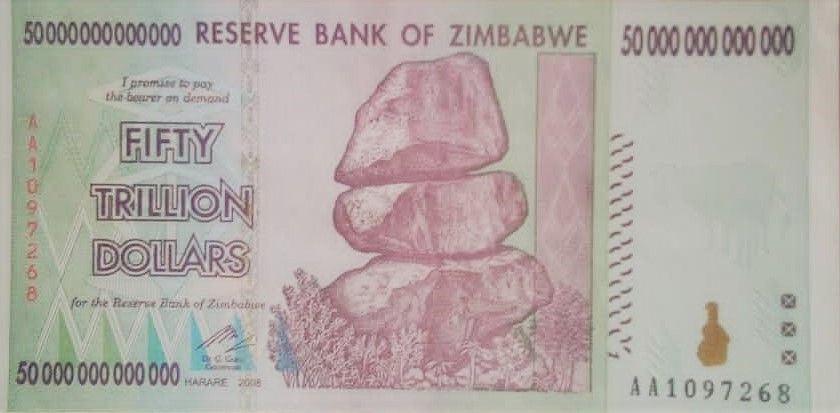

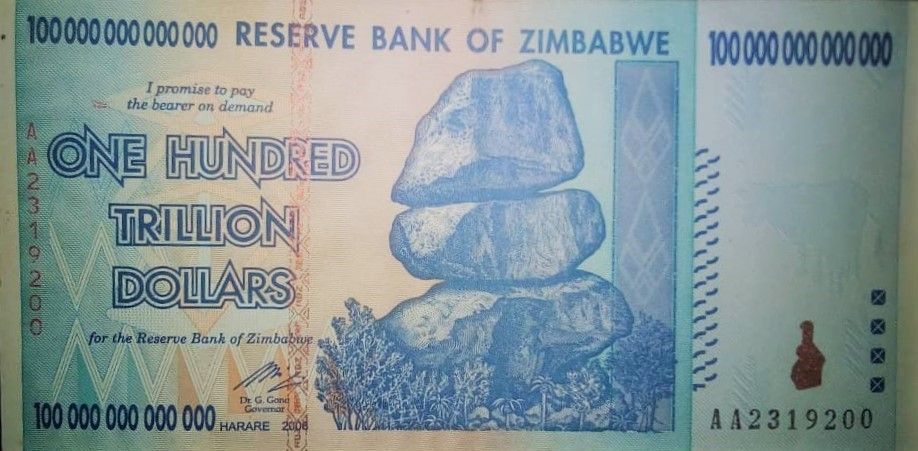

This was followed by nearly a decade of gradually rising inflation. The currency’s value was eroded as a result and the central bank of Zimbabwe began to issue higher denominations of the Zimbabwean Dollar. Between 1993 and 2003, Z$50, Z$100, Z$500 and Z$1000 notes were issued. In the following years leading to the 2008 – 2009 crisis, inflation got out of control and the Zimbabwean dollar was in free fall. In 2009, the biggest legal tender in all history, a 100 trillion dollar bill was issued. At the time, one trillion Zimbabwean dollars was worth about US$0.30 and barely enough to buy a loaf of bread.

A 50 trillion dollar note issued by the Central Bank of Zimbabwe in 2008.

A 100 trillion dollar note issued by the Central Bank of Zimbabwe in 2009.

Having spent my childhood in Zimbabwe, I experienced how the rising inflation in the years preceding the crisis shaped people’s lives. By the time the crisis hit, l had just begun my internship, which gave me some good insights into the impact of hyperinflation on Zimbabwe’s working population and on the productivity of local businesses. This hyperinflationary regime was brought to an end following the abandonment of the Zimbabwean currency in 2009.

What is Hyperinflation?

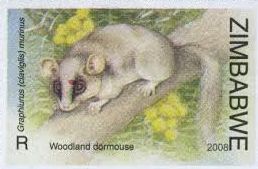

Hyperinflation is a period of currency instability, characterised by rapid uncontrollable price increases in an economy. It is hyperinflation which spiralled prices in Zimbabwe to a point where a local postage stamp for an ordinary letter was priced at Z$375,000 in 2006. By 2008, prices were doubling daily and stamps were no longer printed with values on them.

Zimbabwe – 2008 Woodland Dormouse postage stamp. Source: Rats & Mice of Zimbabwe, rhodesianstudycircle.org.uk, 24 April 2008, http://www.rhodesianstudycircle.org.uk/

At its peak, Zimbabwe’s monthly inflation was estimated to be 79.6 billion percent, translating to a daily inflation rate of 98%, which effectively meant that prices were doubling every 24 hours. This was the second highest inflation ever recorded in history, after Hungary’s 1946 record.

Some Background

In the early ‘80s, the Zimbabwean currency was close to par with the US dollar and the agriculture, mining and tourism-driven economy was thriving. Then dubbed ‘the bread basket of Africa’, the nation was a huge agricultural exporter of wheat, tobacco, and corn to the rest of the continent and beyond.

Between 1991 and 1999, a string of government policies and actions led to a series of shocks that destabilised the economy. By the start of the 21st century, the nation had been ushered into an era never imagined before by the once most stable African economy. The country’s main sector, which is agriculture, was destroyed and exports were significantly hit. Declining food production and manufacturing output meant increased dependence on imports, and with very little export business, so the foreign exchange reserves ran out. Imported basic commodities like fuel became very expensive, and this drove up prices of everything else.

Because of the rising prices, the government had to increase salaries for civil servants, however, the taxes collected today were worthless tomorrow, hence the government resorted to printing more money to pay wages and meet obligations. As the central bank continued to print more money, prices kept going up, and this became a self-perpetuating cycle which led to hyperinflation. These economic missteps significantly undermined the value of the currency and public trust was lost, as pensions and savings accounts were wiped out and access to money in banks became extremely difficult. This brought the banking sector to its knees, which accentuated problems in virtually every sector.

Several efforts by the government to rescue the situation failed, most of which were sure paths to disaster. One that comes to mind is the price controls which were instituted by the government in 2008. Overnight, basic commodities like bread, milk, soap, and sugar disappeared from the shelves in stores and subsequently, perpetual queues became a common sight. By 2009, hyperinflation was at its peak and the country’s status had been reduced to a basket case.

The Experience

Living in hyperinflation meant:

- Paying Z$150 billion for three eggs

- Owing the phone company Z$26trillion on your latest monthly bill

- Paying one week’s worth of earnings for a single day’s bus fare

- Always buying two beers at once because by the time you finish the first, the second would cost you double.

In restaurants, prices increased almost every hour so menu cards were handed out without prices. Occasionally, l went out with my colleagues for team lunches. We would order all our dishes at once and pay the bill upfront, since waiting to pay after the meal came at a price.

Having a meal at a restaurant in Harare, Zimbabwe

It was a matter of living from hand to mouth. Salaries, which were not frequently readjusted to compensate for inflation, became absurdly low and hardly enough to make a living. An average salary could barely fill a wire shopping basket. To make the most out of the salary earned, one had to immediately go to the store and buy a few basics or it would be worth much less by the end of the day. For example, my uncle, a taxi owner, used to take his wife with him on his trips. On receipt of the fare, he would immediately drop off his wife at the nearest shop to buy essential goods and convert any remaining cash into a more stable currency, which could be later converted to pay bills.

For many, it was not possible to have a savings account for one obvious reason; there was nothing left to save. For the few who had disposable income to put in a savings account, the interest rates were extremely high but not high enough to preserve purchasing power. People who had saved all their lives in the hope of a comfortable retirement, had their investments wiped out.

Having one meal a day was not uncommon. An average family would only afford a decent meal once a day, mostly in the evening. It was the lucky few who could afford a decent breakfast. The majority of the food items were out of reach for many, for instance, sipping a soft drink became an unimaginable luxury.

Empty shelves were a common sight. Basic commodities could not be found in shops. Once in a while the products would reappear at controlled prices and queues would form immediately. One would just join a queue, even with no knowledge of what was being queued for.

The retailers were constantly increasing prices and the consumers were ready to pay any price because who knew what the price would be the next day? Prices were increased overnight and sometimes as many as three times during the day. Since the systems were not informatised, items were tagged individually, and as the ‘tag man’ approached, one had to rush and pick the items off the shelf before they were re-tagged. Due to the speculation that prices would rise anytime, hoarding became a common practice, which in turn created more shortages.

And one may wonder, how would one have survived such a troubling time?

It is difficult to comprehend how one survived under such circumstances, but hyperinflation does not happen overnight. Inflation was progressively weaved into the fabric of our everyday living and eventually we became comfortable being uncomfortable. By the time the crisis reached its peak, one would describe us as a resilient nation, by simply observing our way of life. For instance, l still went out to have fun with my friends, although with very little to spend. We laughed and talked the night away and often found some humour in our difficult situation as a nation.

Enjoying a night out with friends

A handful of people received family support from relatives abroad. At the height of the crisis, thousands of professional Zimbabweans, mainly nurses, doctors, technology specialists, accountants and teachers, had left the country in pursuit of better economic opportunities. These expatriates would then send cash back to their families and remittances became the country’s single largest source of foreign income. Family support for as little as US$100 per month would go a long way.

People downgraded their lifestyles – cars were grounded to save fuel. Christmas and birthday celebrations became a luxury, and those in leafy suburbs moved to medium density suburbs and some even migrated to rural areas. Instead of going to professional salons, it was cheaper to go to makeshift salons in backyards. Mostly these were set up by unemployed hairdressers trying to make a living.

Getting hair done at a makeshift salon in the backyard.

Getting hair done at a makeshift salon in the backyard.

Properties were significantly devalued as people resorted to selling assets such as houses and cars to send their children to school and to meet daily living expenses. Expats flooded the property market, buying up houses from people who were desperate for foreign currency.

With basic commodities off the shelves, it became common practise to immediately convert salaries to stable currencies, such as the South African Rand and the US Dollar. With some savings in foreign currency, people would travel to neighbouring South Africa to buy up to 3 months’ worth of groceries for their families.

Some employers introduced various innovative allowances. These included food hampers, fuel or taxi vouchers, lunch packages, phone subscription allowances, rent allowances and school fees packages.

Hyperinflation: At whose cost?

Hyperinflation left a sad legacy. It transferred wealth from wage earners to profit earners. The middle class disappeared and what remained was just the very poor, relatively poor and the ultra-rich. It also transferred wealth from creditors to debtors. The implications for lenders were profound. Banks made significant losses on fixed-rate mortgages, as mortgagors took the opportunity to settle their existing mortgages for next to nothing. Sadly, the group of people who suffered the most were pensioners, who had saved all their lives in the hope of a comfortable retirement. With no human or financial capital, the retirees were left dependent on their families for support.

The Impact of brain drain on delivery of vital services has been remarkable, mostly in the health sector. Patients who got admitted into public hospitals had no guarantee of quality care due to the gaps in staffing. The public health system virtually collapsed with shortages of medical equipment, medicines and personal protective equipment in most public hospitals. With hyperinflation, labour productivity is impacted as resources are channelled to non-value adding duties, such as shop floor workers employed to constantly re-price items. Instead of people spending productive time in their work places, they endured waiting in long and winding bank queues in order to access their salaries before they lost value.

Hyperinflation is a productivity killer.