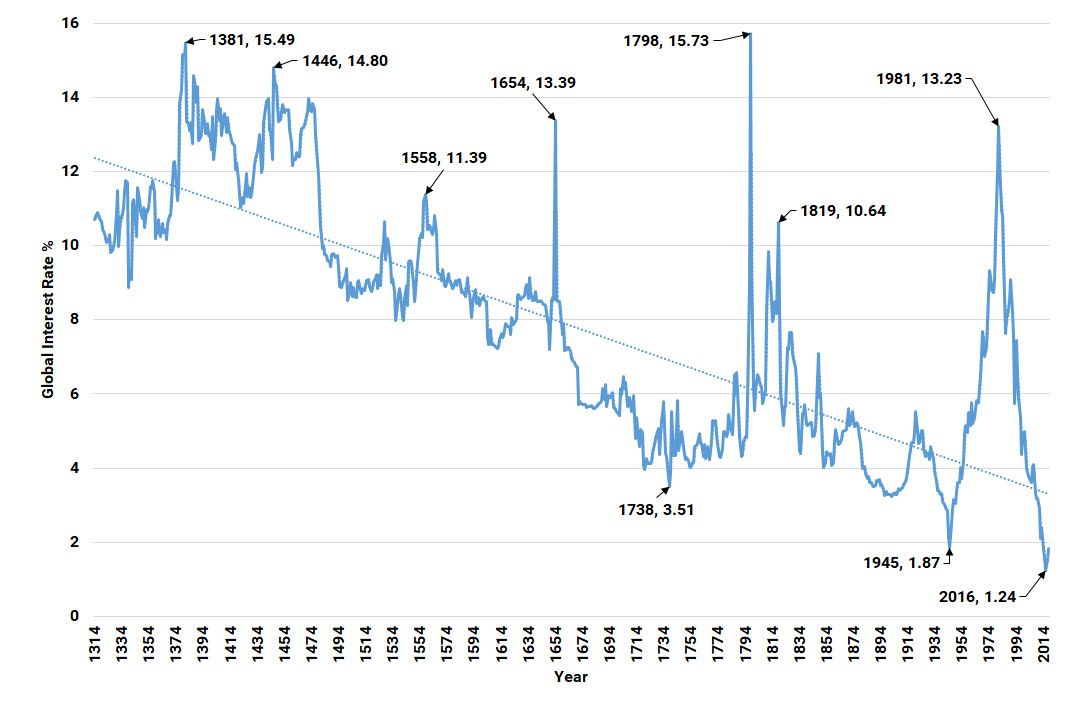

Thanks to the Bank of England, it’s now possible to track global interest rates back to the early 1300s and UK rates back to the reign of Queen Anne. So, we did just that!

Chart A shows global rates over 700 years up to 2017:

Chart A – Long Term Global Interest Rates

Source: Bank Of England & Paul Schmelzing

The compiler of the figures for Chart A, Paul Schmelzing, constructs the data by taking interest rates from the lead economy of the era. This could be, for example, the UK, or the US, or Holland, depending which was the dominant world economy of the time.

Global rates bottomed at 1.24% per annum in 2016 (although Schmelzing’s data ends in 2017 and today, interest rates are even lower).

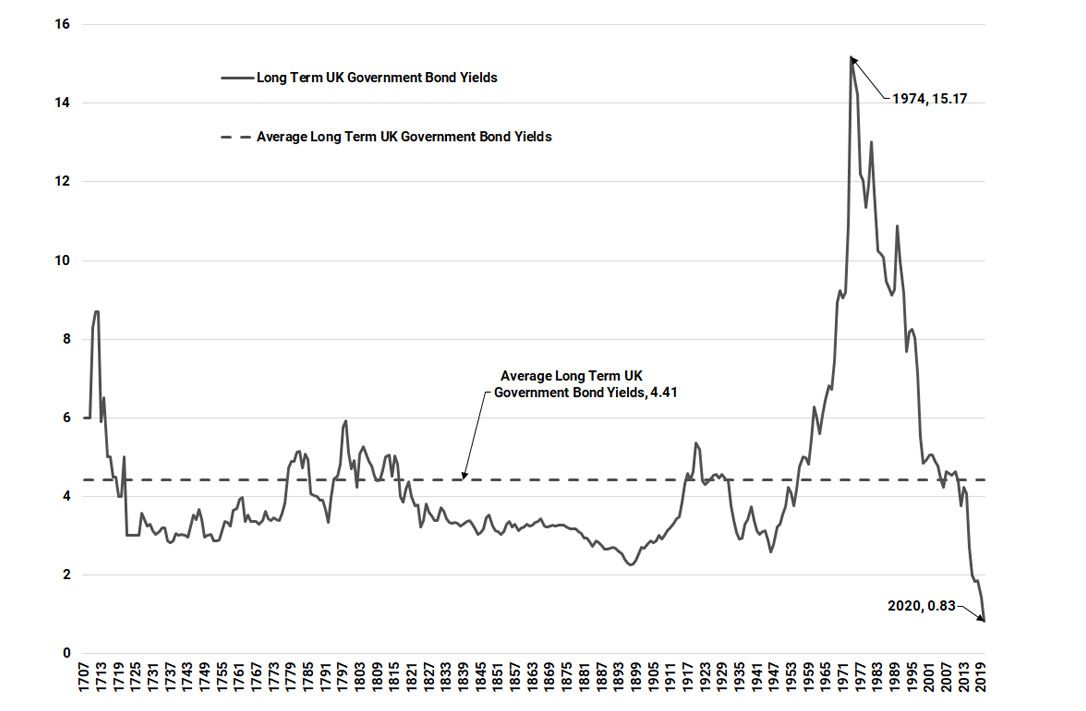

Chart B shows over 300 years of interest rates in the UK, which dropped to record lows in 2020:

Chart B – UK Government Bond Yields from 1707

Source: Bank of England, Bloomberg & Courtiers

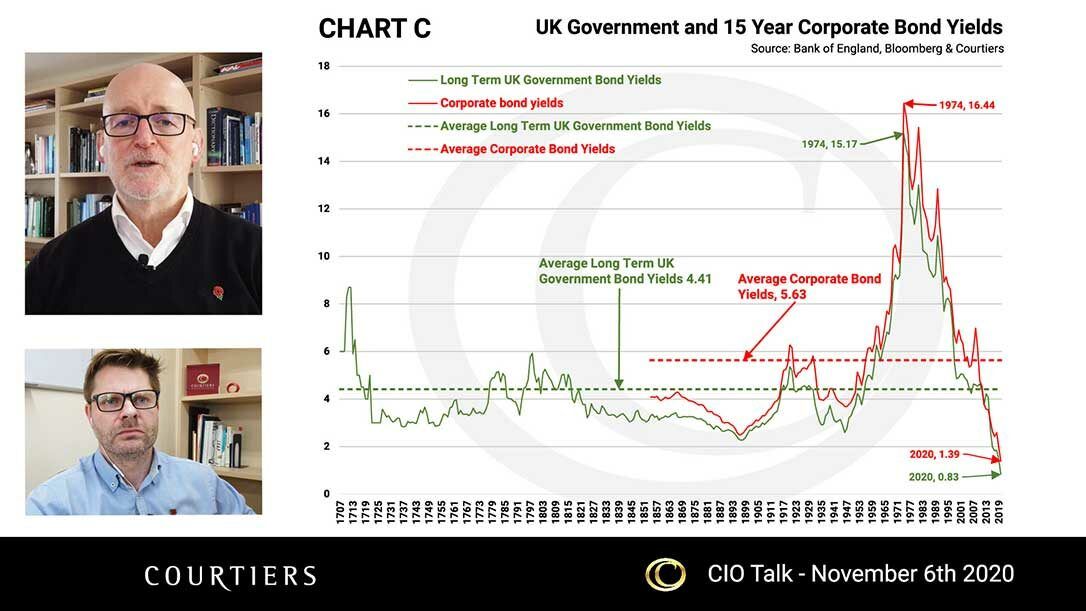

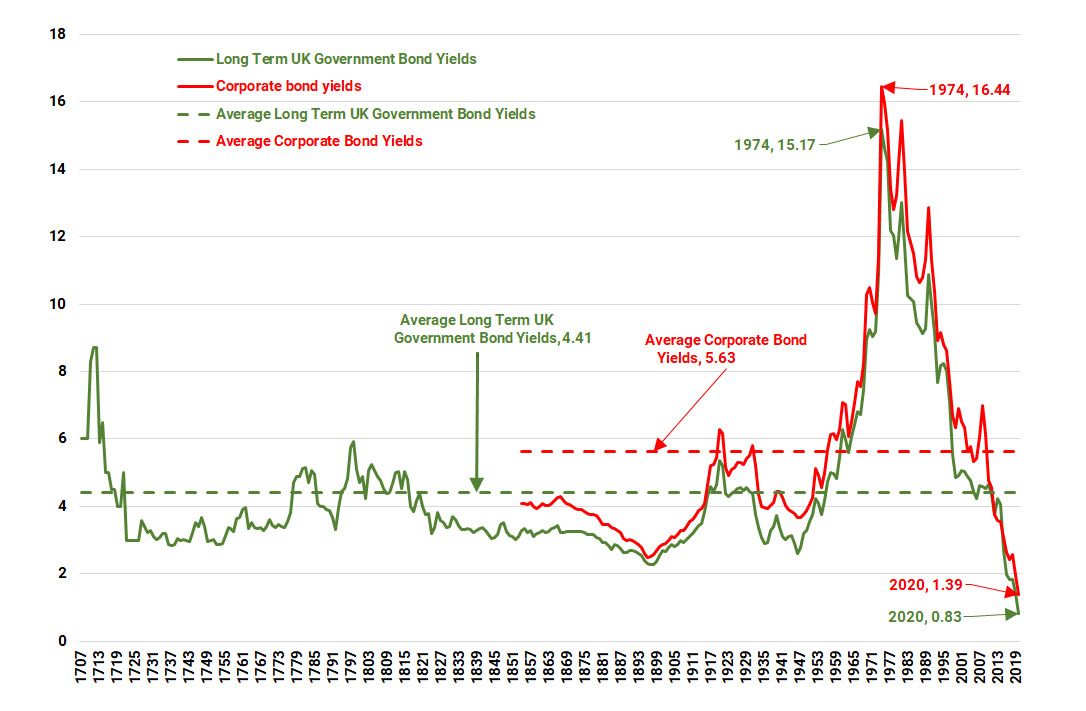

The phenomenon of rock bottom interest rates is not confined to the government sector. Businesses are also able to borrow at record low levels. This is reflected in 15-year sterling corporate bond yields also hitting their nadir in 2020 (see Chart C):

Chart C – UK Government and 15 Year Corporate Bond Yields

Source: Bank of England, Bloomberg & Courtiers

The 40 year fall in interest rates and the bond bull-market have occurred for a number of reasons: –

- Yields shot way above their long-term average in the 70s and early 80s.

- Central banks established their inflation-busting credentials in the 80s by showing a willingness to increase interest rates, in order to meet their goal for limited price rises (normally 2% per annum) within their economies.

- A global savings glut caused by certain large economies running big current account surpluses (China, Japan and Germany in particular), created a demand for high quality bonds, driving prices up and yields down.

- Successive governments gained election on a platform of ‘fiscal responsibility’ (balanced budgets). In other words, Keynesianism died out in the inflationary 70s and was replaced by monetarism.

Monetarism

Under monetarism the central bank raises and lowers interest rates depending on levels of inflation. It’s long been believed that inflation is cyclical and moves inversely in relation to the spare capacity available within an economy. If demand for goods and services exceeds supply, prices rise and, in an effort to curb demand, the central bank increases interest rates. This takes money out of the pockets of consumers and dampens their enthusiasm for purchases.

Monetarism has established its credentials at reducing inflation, but it has proved ineffective at stimulating growth. In other words, when demand is low, and significantly below the level of potential supply within an economy, lower interest rates just don’t seem to stimulate additional purchases. Keynes would call this a ‘liquidity trap’.

Under a liquidity trap, even when you give people more money, either by reducing interest rates or through Quantitative Easing (where the central bank buys assets from the private sector), the extra liquidity is simply saved. One of the reasons for this phenomenon is that ultra-low interest rates only occur when economic problems persist, which reduces consumer confidence and increases precautionary savings.

Monetarism reached its peak post the Global Financial Crisis, which has seen:

- Nominal interest rates approaching zero

- ‘Real’ interest rates running negative

- Investors so spooked by uncertainty that they are prepared to buy short and medium dated government bonds with guaranteed negative returns (and potentially substantial negative ‘real’ returns).

In short, central banks have been unable to encourage additional economic activity through the manipulation of interest rates.

Unfortunately, the effects of monetarism are not the same across the economy. Falling interest rates push up the value of assets, which is a benefit to the wealthy. If those same low interest rates fail to increase demand then consumer spending, and private sector investing, will be diminished to the detriment of jobs and wage levels. In short, falling interest rates make the wealthy wealthier and the poor poorer (at least relatively).

America is normally at the vanguard of any major changes in economic policy. In the 1980s President Ronald Reagan and then Chair of the Federal Reserve Board, Paul Volcker, used monetarism to eradicate US inflation. Margaret Thatcher followed suit in the UK and the formula for running an economy with decent growth, and low inflation (and getting re-elected) was established.

Fast forward to 2020 and the situation is very different. Governments today fear deflation more than inflation. A decade of persistently low interest rates has failed to generate any meaningful pick-up in prices. In the US, the Republicans and Democrats have both realised that government spending will be necessary to drive America’s economy forward and a large government stimulus will be forthcoming, irrespective of who occupies the White House…the only difference between the parties being, who will be the major beneficiaries of such spending?

In the UK, Boris Johnson’s significant 2019 majority was gained because he convinced traditional Labour voters in the ‘red wall’ (the Labour heartland constituencies in the Midlands and North) to vote for him. More monetarism is unlikely to improve the lot of these voters.

In an effort to stimulate the British economy, and for this government to get re-elected in 2024, expect:

- lots of talk about fiscal prudence

- lots of spending on the things that matter to working-class people.

Government spending will do significantly more to boost economic growth than monetarism, but it will push up inflation and interest rates with it. There is evidence of this in recent market movements.

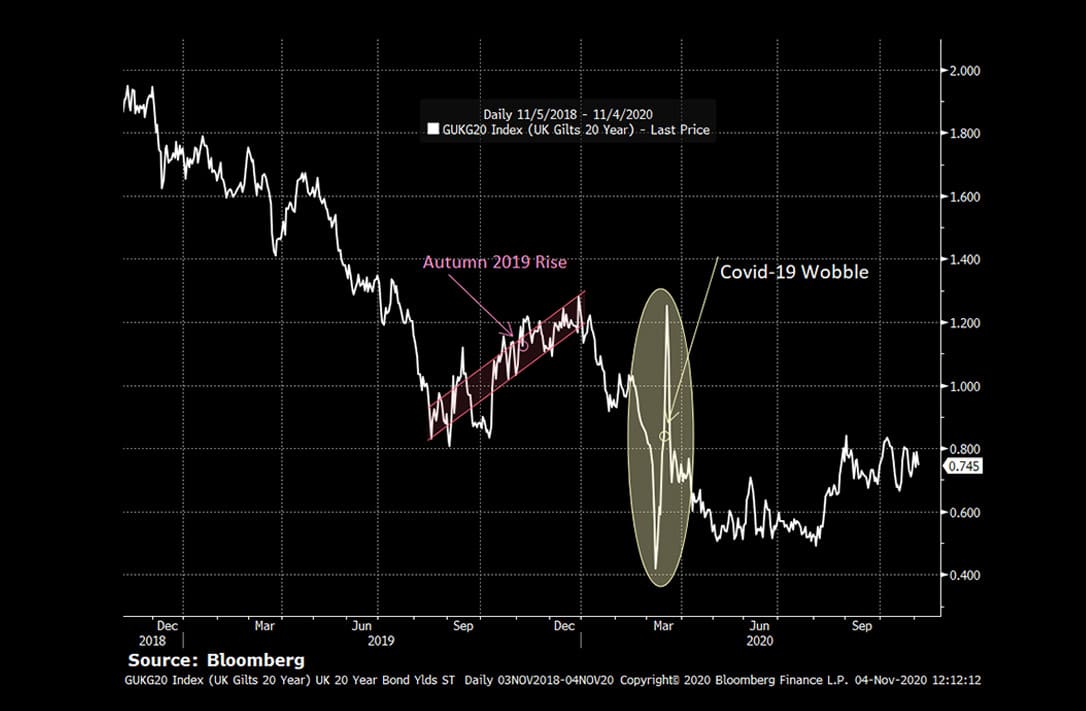

Although long-term trends show decades of falling interest rates, short-term trends show indications that the nadir for interest rates may already have been reached. Chart D below highlights the 2019 autumn rise in 20 year gilt yields, and the incredible wobble in interest rates as the UK was engulfed in the pandemic in March:

Chart D – UK 20-Year Gilt Yields

There is one final compelling argument for avoiding long dated bonds – they make no investment sense whatsoever.

Chart E below shows the UK 20-year index-linked spread. In other words, it shows the spread between the return on 20-year fixed interest gilts (0.74% per annum in the chart) and 20-year index-linked gilts (-2.537% per annum in the chart).

Chart E – UK 20 Year Index-Linked Gilt Spread

As the 20-year fixed interest gilt and the 20-year index-linked gilt are of exactly the same credit quality, the difference reflects the expectation in inflation (RPI) over the next two decades, which Chart E shows in blue at 3.28% per annum.

There are two points to highlight here, which are absolutely astounding:

- 20-year fixed interest investors are prepared to accept so little for lending to the UK government for so long

- Investors in index-linked issues will acquiesce to a guaranteed erosion in the purchasing power of their money of -2.537% per annum, through to 2040 in return for what they perceive as “safety”.

Anybody holding long-dated fixed interest securities for “safety” reasons needs to dramatically re-examine their thinking. Fixed interest investments offer safety in nominal terms, but they offer no safety at all with regard inflation. If inflation returns to normal long-term levels with interest rates following suit, it will create a bond bloodbath in which holders of long-dated gilts will lose over 50% of their capital value. That is not safe!

Needless to say, Courtiers is steering well clear of long-dated bonds and holding the risk-reducing, liquid portions of portfolios in short-dated gilts and AAA rated supranational issues, Treasury Bills and cash. These can be categorised as “safe”.