After eight years of steady economic growth there is talk about whether a UK recession is looming. Anyone that has attended a speed awareness course will recall being told that lower speeds reduce the possibility of an accident and the damage and injury resulting from it. It is a bit like this for the economy. If growth is rapid, then there is a greater chance that the wheels will come off with a nasty recession ensuing.

The recent rate of economic growth in the UK is modest, especially bearing in mind the depth of the recession in 2008/2009. There has been no bounce-back. Current rates of growth are so low that the car is more likely to stall rather than crash.

With regard both equity markets and the global economy, there are some external threats which are obvious, and with regard the UK, there are obstacles particular to our domestic markets.

The external threats include:-

- The growth in Chinese debt and the falling rate of China’s GDP (Gross Domestic Product) growth

- North Korean military posturing

- A tightening of monetary policy (i.e., rising interest rates and reduced Central Bank balance sheets)Conditions that are pertinent to our domestic economy are:-

- Brexit – and in particular, its effect on the UK’s ability for free trade

- The mysterious disappearance of UK productivity growth

- The descent of UK real wage growth into negative territory

In this paper I summarise each of these issues.

1. Debt Growth in China & GDP Slowdown

Chinese debt has grown rapidly over the last 10 years as its Communist government has allowed borrowing to pile-up in an effort to maintain miraculous, double-digit GDP growth.

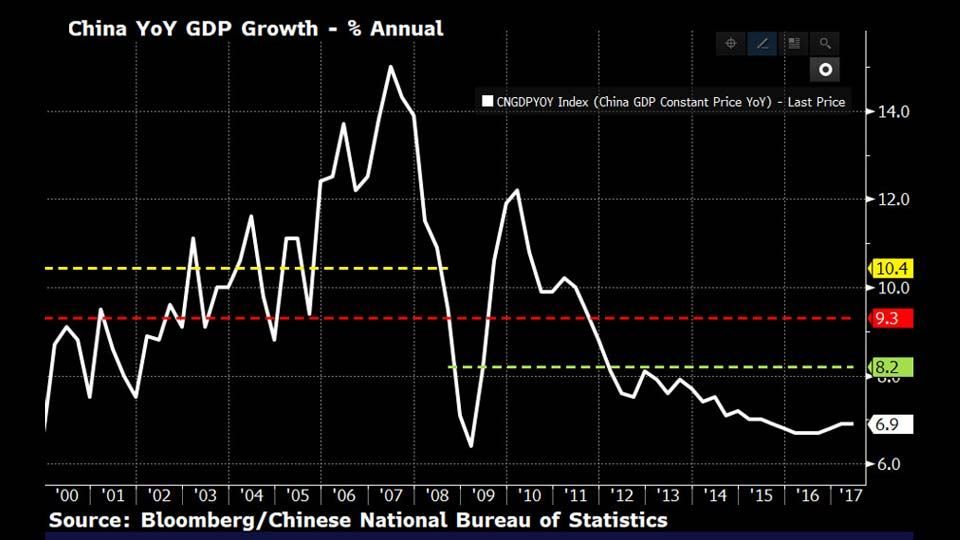

From 2000, the Chinese economy has grown by an average of 9.3% p.a. (Chart 1). Up until the global financial crisis the average rate of growth was 10.4% p.a. and accelerating. Post the global financial crisis, the rate has averaged 8.2% p.a. and is decelerating. The latest rate of annual economic growth is 6.9%.

Chart 1 – Chinese Economic Growth

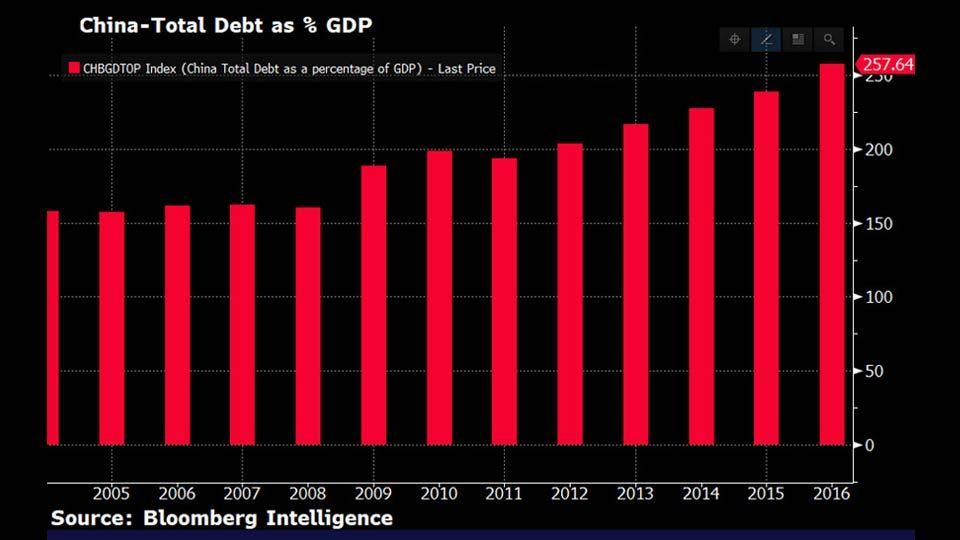

Total Chinese debt has increased from 158% of GDP in 2004 to 258% at the end of 2016 (Chart 2).The breakdown of this debt is shown in Chart 3.

Chart 2 – Growth in Chinese Debt as a Percentage of GDP

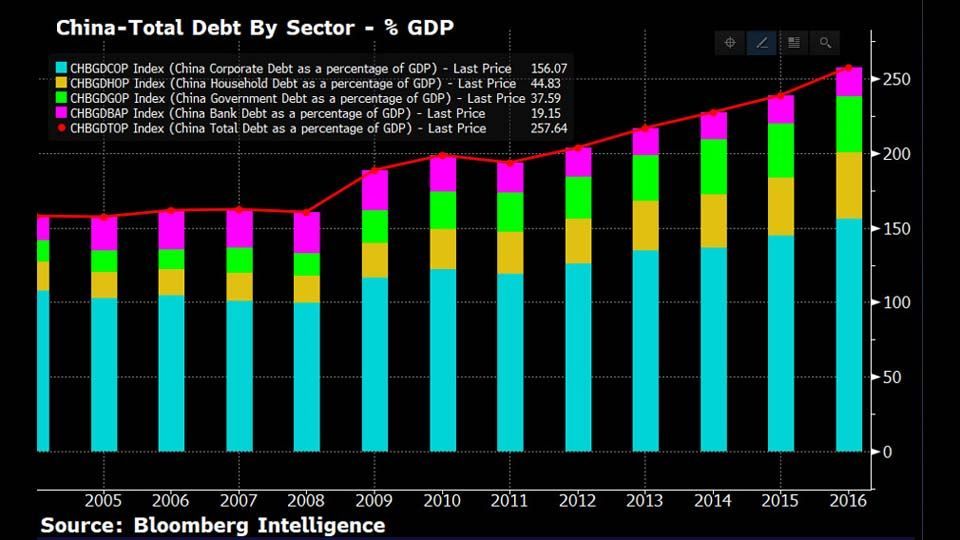

Chart 3 – Total Chinese Debt as % of GDP, by Sector

Borrowing by Chinese corporations forms the largest proportion of total debt (the blue bars). It was 107.81% of GDP in 2004, and is now 156.07% of GDP, a rise of 44.8% in the period. Household debt (the yellow bars), which started at 19.15% of GDP in 2004 is now 44.83% of GDP, a meteoric rise of 134% in the period. That is still a lot lower than in the West (US household debt is 78% of US GDP), but Chinese consumers are catching-up. Government debt (the green bars) has risen from 14.96% in 2004 to 37.59% currently, a rise of 151% in the period. The current level of Chinese government borrowing is still modest by Japanese standards (the International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimates Japanese gross government debt at 239.18% of GDP at the end of 2016 – although this drops to 119.78% after taking account of Japanese government reserves) but, again, the Chinese are catching-up fast. Chinese bank debt (the pink bars) has changed very little. It was 16.21% in 2004, and now stands at 19.15% of GDP (a rise of just 18% in the period). What is of more concern for Chinese banks is the amount of bad debts on their balance sheets. This is as a result of propping-up failing, frequently government sponsored, businesses.

There is still scope for significant appreciation of Chinese GDP, but the days of 10% per annum growth are gone. Even the Chinese authorities have realised that they need to settle for a more sober 6% per annum. This seems to be the target for the Chinese Communist Party, perhaps because it believes this to be the level that will keep the populous happy.

The low hanging fruit of Chinese economic expansion has already been picked. From here onwards, China will have to do more than simply provide the low-cost, low-skilled labour that works the factories producing the world’s cheap goods. If China wants to genuinely close the gap between its GDP per head ($8,113 per annum) and US GDP per head ($57,436 per annum) then it will have to start competing in the markets for higher tech products.

2. North Korea and Military Posturing

I don’t think there is any subject that lends itself to so much cause of speculation in markets as war, or the threat of war (economists prefer the phrase “geopolitical risk”).

No one can be certain of what will happen in North Korea. However, a little background on the Non Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons Treaty (NPT) may be helpful. The NPT has been in force for nearly 50 years. It recognises five Nuclear Weapons States (NWS) which are:-

- US

- Russia

- China

- UK

- France

There are many other signatories to the Treaty, but these are countries that do not have nuclear weapons capability. They are called the Non-Nuclear Weapons States (NNWS). The NWS and NNWS have agreed not to supply or procure nuclear weapons.

Three countries that refused to sign the Treaty are India, Pakistan and Israel. They all now possess nuclear weapons.

North Korea, which had ratified the NPT in 1985 only to withdraw from it in 2003, has pursued a goal of becoming a Nuclear Weapons State. It conducted its first nuclear test in 2006. Its last test was on 3rd September 2017 when it claimed to have successfully exploded a hydrogen bomb.

The Kim dynasty has controlled North Korea for three generations. It is oppressive, like most dictator families, and has turned its country into an economic graveyard. The slides from our 2014 client seminar showed the development of China and the region, expressed as the amount of light emitted by cities and how this had changed between 1992 and 2010. North Korea shows as a black void on the map. It has hardly developed at all.

Development shown by changes in light emission between 1992 – 2010. North Korea shows as a black void on the map.

Kim Jong-un does not trust America. He will have noted that the US government has tinkered with domestic policies in countries that it considers “unfriendly”, and in certain cases instigated regime change (Iraq and Libya). Kim Jong-un sees the possession of nuclear weapons as the best means of ensuring that the US does not interfere in North Korean affairs. Whatever he says, Trump cannot instigate military action against North Korea without the risk of an Asian nuclear holocaust, with the subsequent loss of millions of lives.

The NPT is a good example of an international treaty that has worked well. Since the bombing of Nagasaki on 9th August 1945, 72 years have lapsed without a nuclear weapon being used in warfare. The principle of MAD (Mutually Assured Destruction) has been effective. Kim Jong-un may seem like an unhinged, despotic tyrant to us, but in the context of maintaining the Kim Dynasty, his actions make complete sense. The principles of MAD work for him.

As neither the US, China or Russia have been able to stop the North Korean nuclear weapons programme, or gain agreement for North Korea to revert to being a non-nuclear weapons state (and these three super-powers are actually in agreement on this), then the only other logical step is probably to recognise North Korea as an NWS, although the fear of the existing signatories to the NPT will be that this may encourage other nations to aspire to a similar goal.

Complicated? – you bet! Even the self-acclaimed master negotiator in the White House seems stumped on this one.

Despite the obvious concerns of ordinary people all around the globe, about the situation in the Korean peninsula and the risks of a nuclear war, investors should bear in mind that the history of mankind is littered with conflict. And despite there being no nuclear attacks for 72 years, there were plenty of rumours of such in the period, especially during the cold war.

There is very little anyone can do about geopolitical risk. It is difficult to quantify1 and its effects on asset prices are mainly as a result of sentiment. Baron Rothschild is credited with saying “buy when there is blood in the streets”. That was during the Napoleonic conflicts. War, and the threat of war, are not new.

We should not let tensions in the North Korean peninsula affect our investment decisions because, despite the risks, the conflict is likely to eventually end, in which case there may be a boost to asset prices, as happened in 1991 when the Gulf War concluded.

1In a paper in the Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol 51, no. 2 (Feb 1937), PP209-223, John Maynard Keynes referred to war as amongst those matters about which “…there is no scientific basis on which to form any calculable probability whatever. We simply do not know.”

3. Monetary Policy – Belt-tightening

Post the global financial crisis, monetary policy has been very accommodating, i.e., it has been designed to help the economy grow. Short-term interest costs, as denoted by base rates, have been at record low levels around the world. Further, in order to push down long-term interest rates, central banks have been buying bonds.

Some central bankers are expressing a concern that these accommodative policies will, if not curbed, prove inflationary. At the Bank of England MPC (Monetary Policy Committee) meeting of 13th September, two of the nine members (Ian McCafferty and Michael Saunders) voted to increase Base Rate to 0.5%. The other seven voted for it to remain unchanged at 0.25% per annum.

Inflation is the outcome when supply within an economy is unable to meet demand. In these circumstances, consumers compete for a limited supply of goods and services and prices rise accordingly.

One indication of supply constraints is when the number of available workers in an economy declines, which happens when the rate of unemployment is very low.

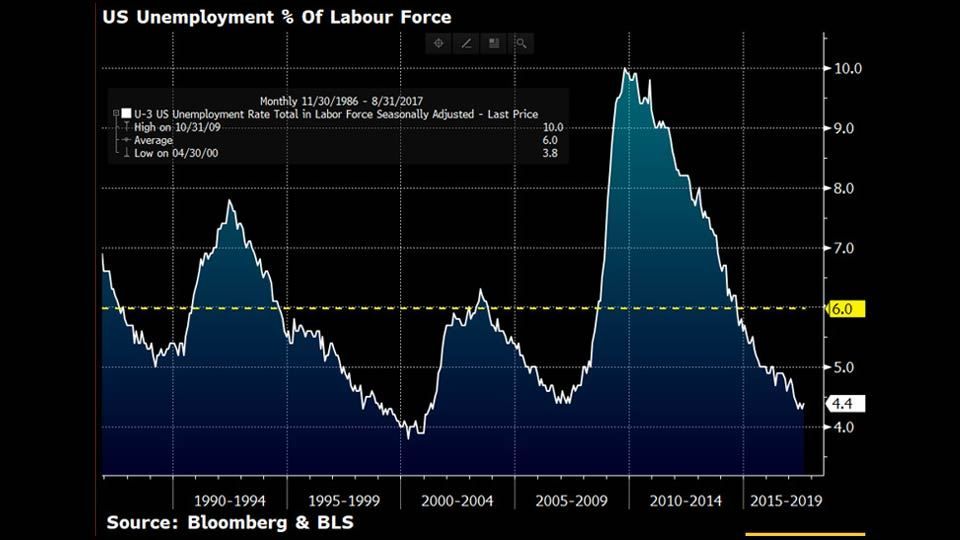

Since 1986 the rate of US unemployment has averaged 6%. It is currently 4.4%, not far above the record low level of 3.8% reached in April 2000, and significantly lower than its peak of 10% in October 2009, as highlighted in Chart 4.

Chart 4: US Unemployment

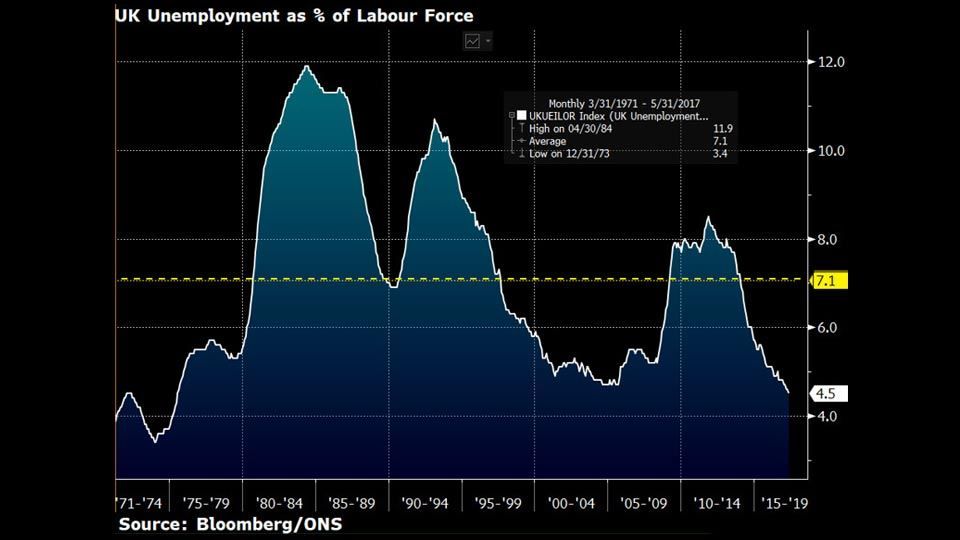

Unemployment is also low in the UK, as shown in chart 5.

Chart 5: UK Unemployment

UK unemployment, at just 4.5%, is at its lowest level for over 40 years and is significantly lower than its average of 7.1% from March 1971 to May 2017.

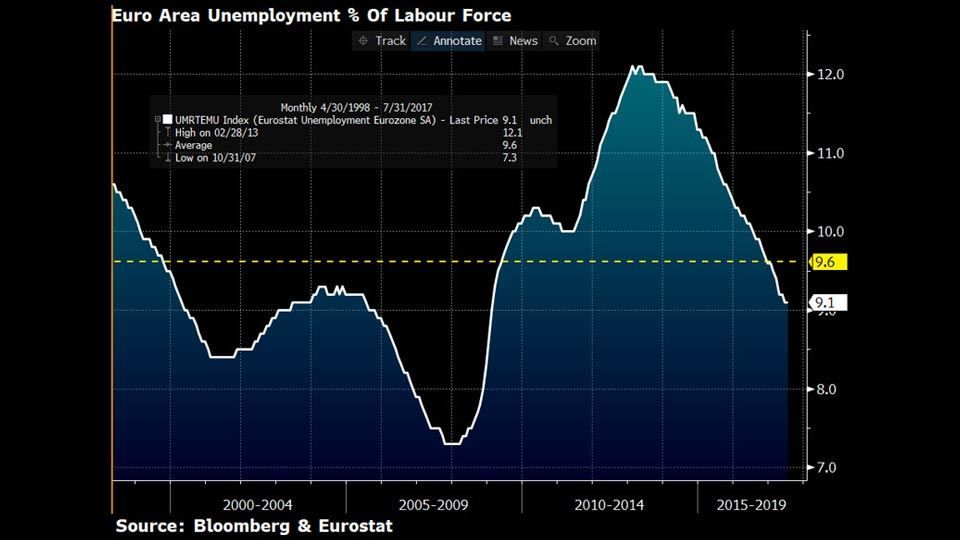

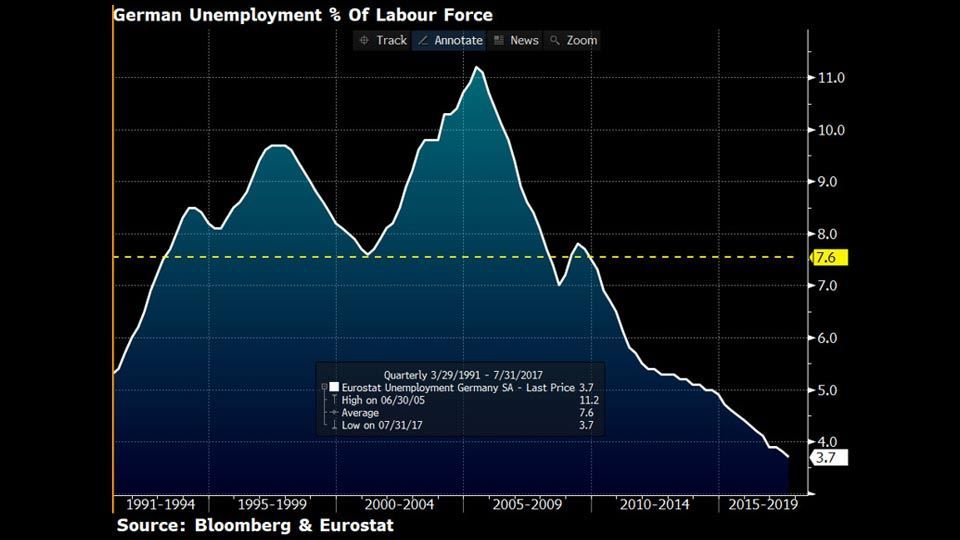

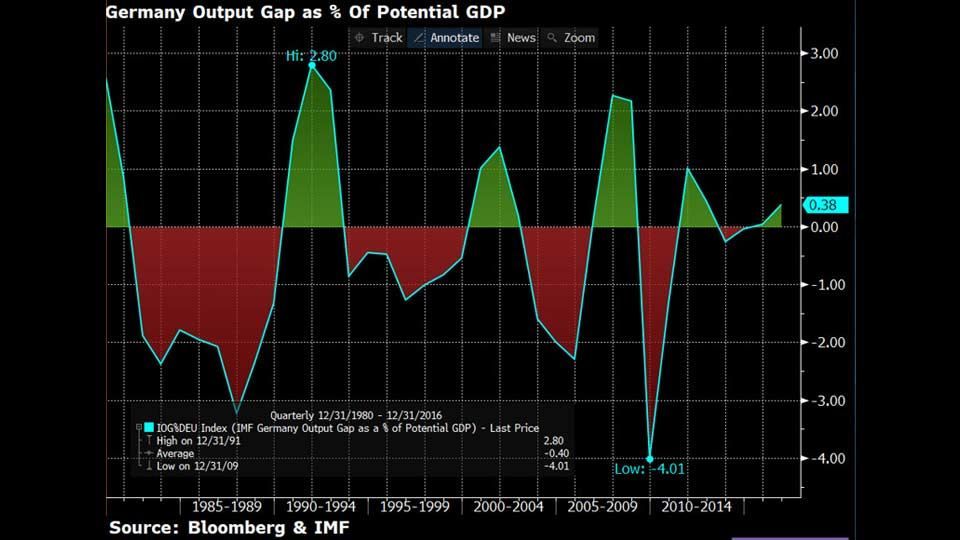

Unemployment is higher in the EA (Euro Area) at 9.1%, although Germany, its biggest member, is experiencing record low unemployment of just 3.7% (see Charts 6 and 7).

Chart 6: Euro Area Unemployment

Chart 7: German Unemployment

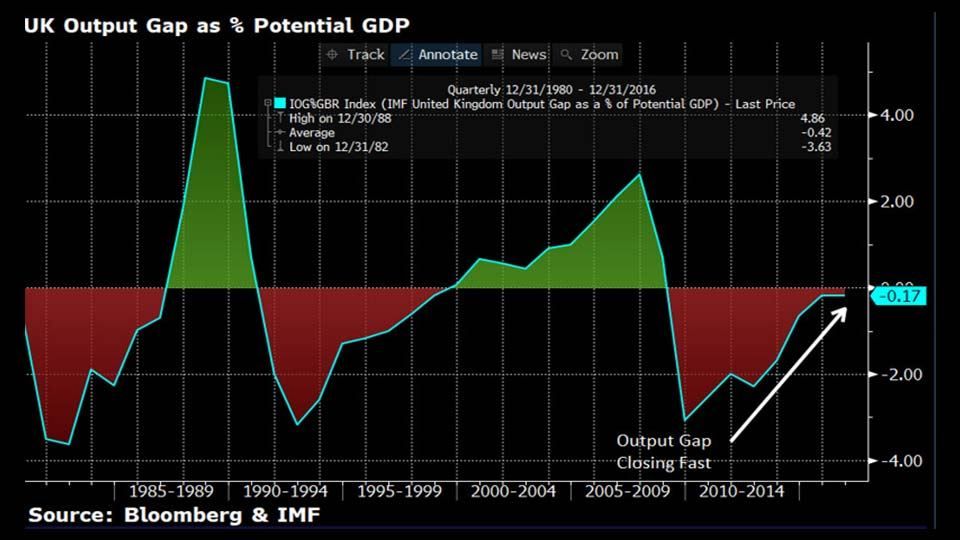

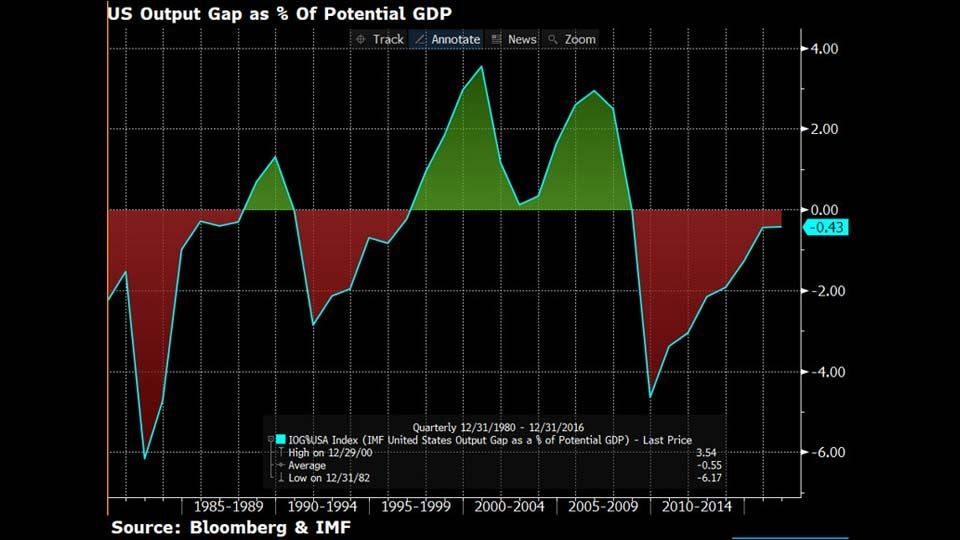

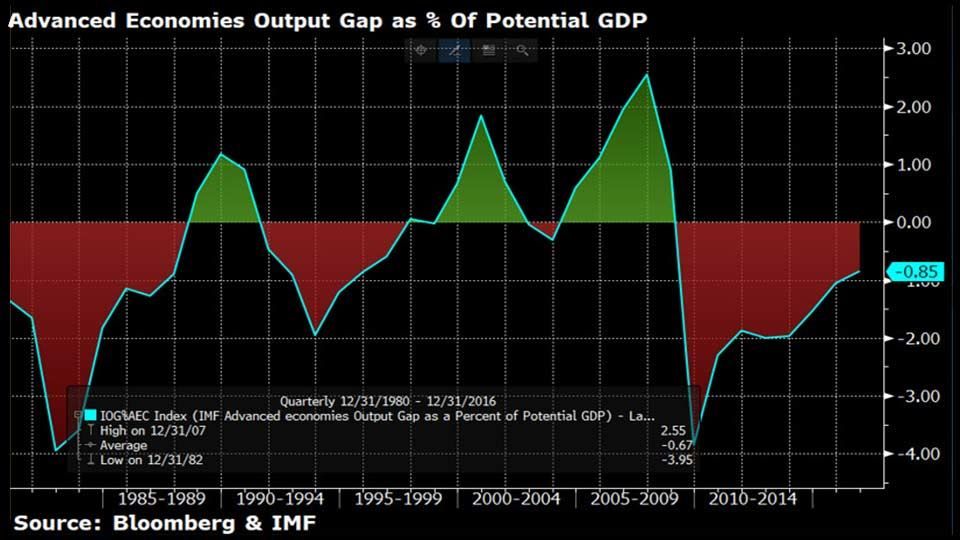

Aside from the unemployment figures indicating limited increased supply potential, the IMF (International Monetary Fund) estimates show just a small negative output gap2 for the UK and US, whilst Germany’s demand now exceeds its supply.

This reducing output gap is fairly consistent, as indicated by Charts 8-11 below which shows the output gaps for the UK, US, Germany and advanced economies generally.

Chart 8: UK Output Gap

Chart 9: US Output Gap

Chart 10: German Output Gap

Chart 11: Advanced Economics

It is against this backdrop of falling unemployment, reduced output gaps and inflation recovering to more normal long-term levels that central bankers will be keeping interest rates under close scrutiny. The Fed (US Federal Reserve Board), the ECB (European Central Bank) and the BoE (Bank of England) have all indicated that future monetary policy will be less accommodative.

2 The “output gap” is a measure of the actual output of an economy compared to the potential output. It is calculated as actual GDP, minus potential GDP, divided by potential GDP. If the figure is negative, it shows that supply is adequate to meet demand, but if it is positive, then it indicates that an economy cannot meet the demand of its consumers – a situation regarded as inflationary.

4. UK Future – Brexit

On 22nd April 2016, I issued a piece entitled “Britain and the European Union – In or Out? The Facts and Fiction”. In that note I provided a lot of detail on the UK’s trading relationships with the EU and the rest of the world.

The EU is the biggest single market in the world. In 2014, EU GDP, at $18.53 trillion, was equivalent to 23.98% of total global GDP (see page 4 of my note of 22nd April 2016). In the same year, the US produced $17.35 trillion (22.45% of global GDP) and China, $10.36 trillion (13.4% of global GDP).

The EU negotiates and applies terms and tariffs on imports from its external trading partners. It is only a free-trade zone for its own members. When the UK exits the EU it will need to ratify new agreements with Europe and strike its own trade deals with the rest of the world.

In the long run, Britain may be more or less successful outside of the EU. Only time will tell. But in the short-term, the uncertainty will rattle UK businesses, which are likely to reduce investment. The price of a better future for the UK outside of the EU (if there is one) will be a short-term shock to the economy. The only thing in doubt is just how big that shock will be.

Politicians can help minimise Brexit’s impact on British business by formulating the leaving terms fast and clarifying exactly what the UK’s trading relationship with the EU will be from 2019 onwards. In the meantime, the potential for UK markets to be disrupted at every toss and turn of the negotiations is high. Brexit will increase volatility in UK stock and bond prices, and sterling.

5. UK Productivity Growth – Mysteriously Disappearing

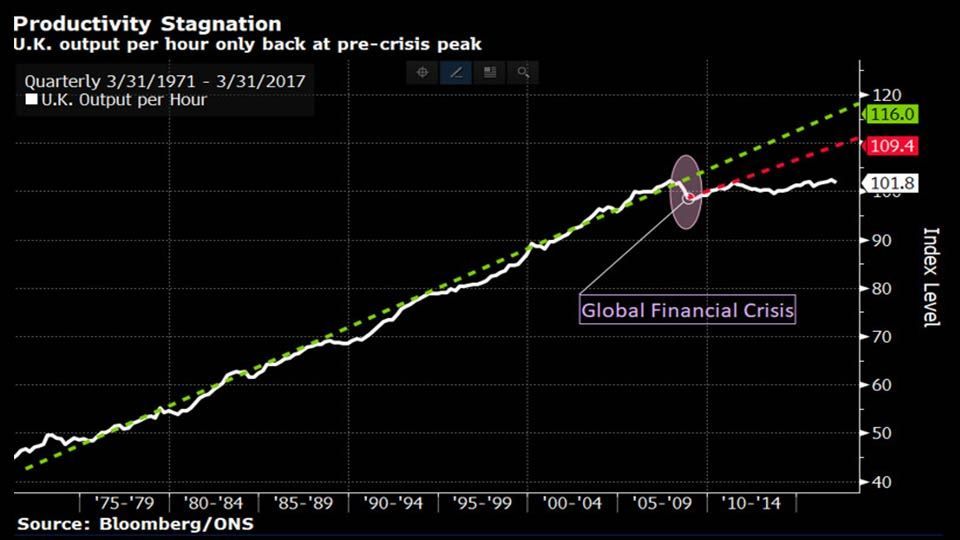

Nobel Prize winning economist, Paul Krugman, once said that “productivity isn’t everything, but in the long-run it is almost everything” (The Age of Diminishing Expectations, 1994), which is a bit worrying because the official data show UK productivity stagnating post the global financial crisis.

Chart 12 below shows the trend of UK output per hour from March 1971 to March 2017.

Chart 12 – Trend In UK Productivity

The solid white line shows the trend in UK productivity. The green dotted line projects where UK productivity would have been if the pre-crisis trends had continued. The dotted red line shows where productivity would be if the post-global financial crisis recovery had continued.

For 35 years from 1971 to 2006, UK productivity (output per hour worked) increased nicely. But it declined during the global financial crisis. Productivity began to recover in the latter part of 2009 although at a slightly lower trend growth rate compared to the pre-crisis pattern, but around 2010 productivity growth stalled completely and has moved sideways ever since.

To put these trends in context, if output per hour had continued at its pre-crisis level (the green dotted line) then output per head today would be nearly 14% greater than the current level. Even if the post-crisis temporary recovery in productivity had continued (the red dotted line), then output per head would be 7.5% higher than it is now. If you believe the figures, the UK has suffered a huge deviation from its long-term trend in productivity.

The most common reason given for the lapse in productivity gains is that post the global financial crisis the UK has boosted employment in low skilled jobs to the detriment of high skilled jobs. The effect is that we have more people in work, but they are less productive. New evidence for this is all around us – with the boom in demand for services, the service industry has taken on lots of lower paid employees (such as in the fields of catering and entertainment).

But there is another side to this story. Today, we seem to have ready access to a range of services and applications, invariably delivered electronically, that were simply not available 10 years ago. At a meeting with our own Head of IT on the 18th of this month, we looked at a service proposition to deliver storage and speed at a level which, just 5 years ago, would have cost 10 x what we are being asked to pay today.

Lord King, former Governor of the Bank of England, makes the point that we put far too much faith in the accuracy of economic data3, which in many instances is simply our best attempt at measuring total activity that comprises billions upon billions of complex trades and interchanges. This is why we cannot even be certain that the figures we have applied to past activities are accurate, never mind the forecasts. To make things even more difficult for economists, some transactions may confer benefits to one or more of the parties involved without necessarily creating a monetary exchange, in which case the utility cannot be measured. Search engines and reference facilities, such as Wikipedia, fall into this category because we have the benefit of accessing information and data, but there is no direct transaction cost.

There is another side to this. Productivity measures output, not necessarily utility for improvements in welfare. My ability to watch TV when and where I want, access any music at any time, and be able to work from home as though I was sitting at my desk in the office may be creating enormous improvements to my standard of living which are simply not being reflected in the economic figures.

If the productivity figures for the UK are accurate, and the trend continues, then output will likely stagnate (and as Chart 5 shows, we haven’t got lots of under-utilised labour to throw into the economy to generate growth) in which case wages and company profits will also stagnate. If, however, you take a more optimistic view and regard the productivity puzzle as at least partially being a result of our inability to accurately measure the digital economy, then there are grounds to be optimistic.

3In his book “The End of Alchemy” Lord King says, “There is a seemingly insatiable demand for economic forecasts. Newspapers and television are only too willing to print the latest forecast of, say, national income with a degree of precision that beggars belief and far exceeds the ability of statisticians to measure it. And at the end of each year prizes are awarded to the forecasters who turned out to be the most accurate. It makes as much sense as it would to award the Fields Medal in mathematics to the winner of the National Lottery” [Page 122 of paperback edition published in 2017 by Abacus].

6. UK Real Wage Growth

Emperor Augustus was clever. He understood that his ultimate source of power was the people, which is why he maintained the grain dole. The modern equivalent is for the average UK worker to participate in the country’s economic prosperity. If we assume that the long-term trend GDP growth rate in the UK is 2% p.a., and that the Bank of England and the Government are successful in implementing policies to keep inflation at 2% p.a., then the nominal rate of GDP growth in the economy will be 4% p.a. (2% inflation plus 2% real growth).

If nominal wages rise by 4% p.a. (2% p.a. “real” after adjusting for inflation) then workers would maintain a consistent share of economic output and enjoy a steady increase in their standards of living.

Unfortunately, post the global financial crisis, and as a result of falling GDP, redundancies and austerity, the average rate of real wage increases was negative between 2008 and 2014. In other words, even though employees may not have taken an actual hit to nominal earnings they were, nonetheless, worse off because inflation eroded the purchasing power of their money (see Chart 13 below). As will be noted from the chart, we have relapsed into negative territory for real wage growth.

Chart 13: Real wage increases/decreases in UK

The problem for employers is that if there is no improvement in output per hour then any increases to workers’ wages will be at the expense of profits, or passed on to the consumer through rising prices (i.e., it would be inflationary). Productivity increases are important because they enable workers to get extra money without creating inflation, or reducing company profits.

It is possible, of course, that productivity and/or GDP figures and/or inflation have been miscalculated for the last 10 years. Perhaps there has been no decline in real wages and everyone is better off. I doubt that, but my views are irrelevant, what matters is the views of millions of workers that believe they have been short-changed over the last decade and that the Government has broken the modern day equivalent of the “grain dole” promise, i.e., the assurance that real economic growth will continue and that workers will benefit from it.

If UK workers believe the authorities have “stored up” riches for the wealthy and upper classes then, at some stage, they are likely to rebel by electing a leader that will unlock the grain stores and distribute the contents equitably. Perhaps Jeremy Corbyn is that leader?

The UK Government will be hoping that real wage increases move out of the red pretty quick, which is why they are starting to talk about removing the cap on public sector wages.

If populism results in even the mainstream, non-populist governments becoming more generous with regard wages and benefits, then the ensuing erosion of the health of public finances is likely to prove inflationary and push up UK interest rates.

Summary

If I had written this type of article at any time in my professional career, which began way back in the ‘70s, I would never at any time have had trouble finding a range of issues with which to “spook” investors. Today is no different.

Some of the issues I have mentioned are completely independent of each other. The effect of the Korean crisis on UK productivity is most likely indirect and minimal. But some issues combine to make a bumpy road for the economy and markets.

Brexit will not help the short-term path of real wage increases, which means that these problems combined (Brexit and falling real wages) are likely to prove even more disruptive and add to volatility in asset prices.

In a couple of years it will be interesting to look back to see how each of these problems has been developed or solved. In the interim, we are being more cautious than normal with our asset allocation, especially with regard the bond market which is the sector that we believe has the potential to deliver the biggest shock of all, and, as always, we are remaining broadly diversified.