Private equity is one of the most contentious subjects in business at the moment. While proponents praise it for turning around failing companies and for its effective use of capital, critics say it shows the worst facets of capitalism – uncaring to workers and to the wider community, while heaping excessive rewards on the few. But either way, anyone reading the business pages recently could hardly have avoided coming across it.

Keen to dig into the subject following a recent Courtiers video interview with CIO Gary Reynolds, I wanted to know more about what Gary thought of private equity. And in particular, whether he saw it as a suitable asset class for Courtiers to invest in.

Private equity on a roll

Buoyed by low interest rates, which make it cheap to borrow money, private equity firms have been building up significant war chests. 2021 has seen them begin to deploy this in earnest. The UK market, which overseas private equity firms especially see as undervalued following the stock market collapse in 2020, is regarded as particularly attractive.

Private equity’s interest in the UK is already turning into reality on the ground. Recent examples of UK companies acquired by private equity include; the AA, John Laing, and St Mowden Properties. Morrisons, one of the country’s largest supermarkets, is currently the subject of a fierce bidding war by two US private equity houses.

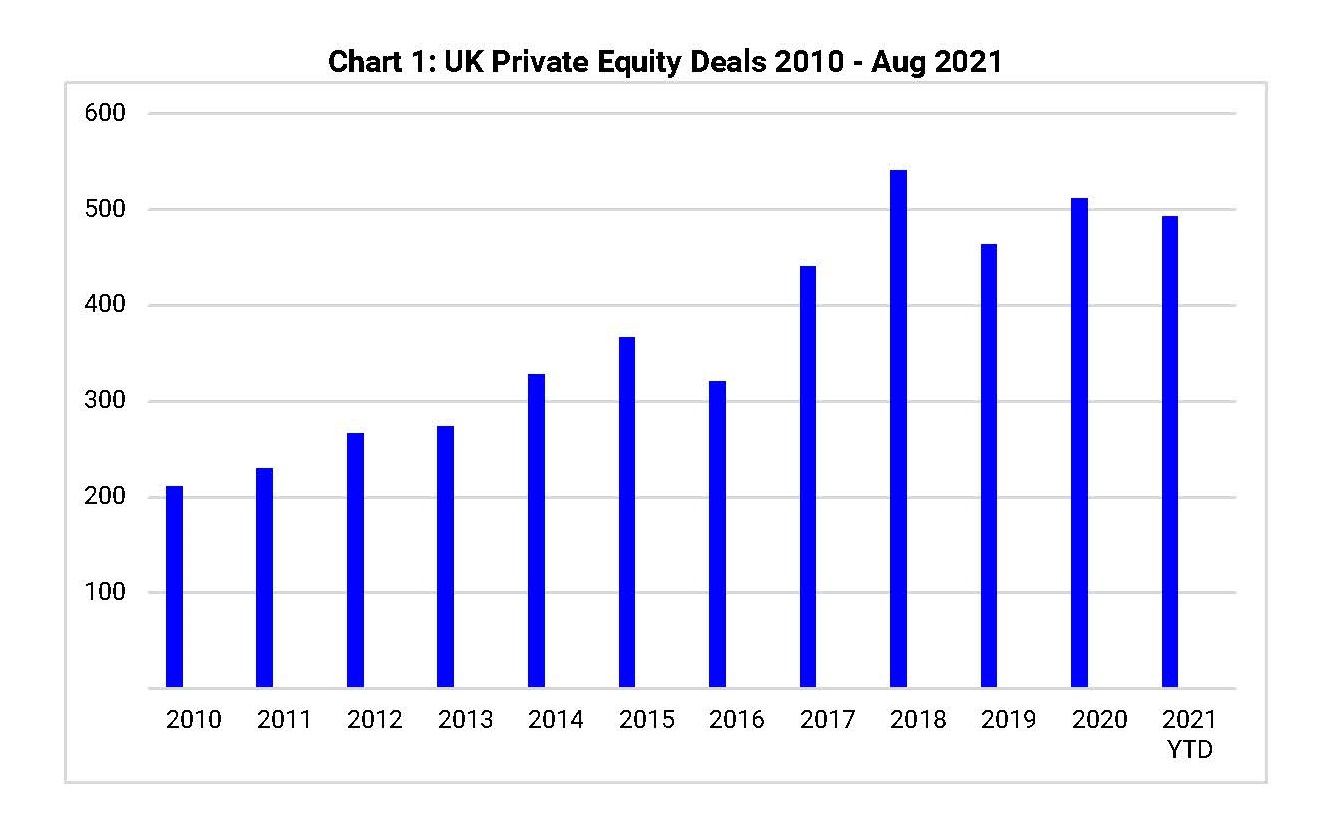

Research by KPMG confirmed that UK private equity investment is in rude health, with deals in the first half of 2021 reaching levels not seen since 2017. According to KPMG, 785 deals were completed worth a total of £73.7bn. Research by Refinitiv confirmed this, with the number of deals up to the end of August already exceeding the number completed in the whole of 2019, now fast approaching the total for 2020 (see Chart 1 below.)

Source: Refinitiv

A significant departure

At the end of August, in a significant departure, the state-backed pension fund Nest said it planned to invest £1.5bn in private equity funds by 2024, with Nest Head of Private Markets saying it offered both “strong returns and diversification.”

Turning to Gary, I wanted to know whether, given that a traditionally cautious body like Nest is eyeing up private equity, he found the attractions of private equity similarly alluring? And with private equity noticeably absent from Courtiers investment portfolios, what would it take to persuade him that this asset class was a suitable one for Courtiers to invest in?

Gary’s views

I started by asking Gary straight out for his view on private equity. “I think it works at some levels,” came his nuanced response.

While Gary recognises the huge success of private equity giants such as KKR and others (“the new masters of the financial universe” as he puts it) this is a far cry from saying that private equity is the right type of investment for Courtiers. “You have to remember that for every firm like KKR that is successful, there will be even more that didn’t work out,” he adds.

I wondered whether Gary might be persuaded by the argument that private equity offers investors access to a range of companies and assets that those, who are restricted to companies in the public market, are denied. By not investing in private equity could Courtiers clients be missing out on juicy returns?

“Our investors are not necessarily after juicy returns,” replies Gary. So rather than clients demanding that Courtiers invests say 15% of the portfolio in private equity, Gary says Courtiers clients tend to be “investing to a goal”. “It’s about lifestyle for the private client, it’s being able to do what they want with their capital for the rest of their lives, meet their base standard of living, enjoy luxuries and leave something to the children and grandchildren. That’s what they want to do, not shoot the lights out.”

Managing blind

Gary clearly knows and understands Courtiers clients, but his reluctance to embrace private equity goes further. While publicly listed companies face constant scrutiny from investors, private equity firms are notoriously secretive. This lack of transparency is not something that sits easily with Gary. “I like visibility, I like to see who has got our clients’ money. I like to be very clear about it.”

So it hardly comes as a surprise when Gary, who heads up the investment team at Courtiers that has long championed risk-adjusted returns – returns that take into account the risk taken in generating them – baulks at the prospect of investing in assets where measuring and assessing that risk is likely to be nigh on impossible. In his words, “You are managing it blind,” which quite apart from his other misgivings, “is something our clients might not be willing to allow us to do.” Gary makes it clear that the inability for investors to get their money out easily – it is often tied up typically for two or three years, he says – is another off-putting factor. As is “the huge amount of leverage (borrowing) and very little liquidity” associated with one of best known aspects of the private equity playbook – the leveraged buyout.

Beware of investment fads

Given Gary’s vast experience, both of markets in all their moods and various investments “fads” that have come and gone over the years, it is no surprise to me that he has absolutely no interest in being part of this or any investment in-crowd, or jumping on whatever is the latest fashionable investment bandwagon.

Gary quickly reels off three such periods when to paraphrase Keynes “the markets remained irrational longer than investors remained solvent”– the residential property boom of the 1980s, the Dotcom bubble of the late 1990s, and the first decade of this century when hedge funds ruled the roost – all of which, in retrospect of course, predictably ended in tears for many investors.

If anything, Gary sees Nest’s announcement that it now sees private equity as attractive, as a sign that rather than embracing private equity investors should look the other way. “The government is always late to the party,” as he puts it, going on to suggest that Nest will end up “with egg on its face.” “Once a government-backed institution decides they have to move into a certain asset class, it’s probably a signal that other people should get out.”

More losers than winners

Yes, he accepts there is a chance that by investing in private equity, an investor could hit the jackpot. But drawing on a sporting analogy Gary says, it’s a bit like saying if you don’t bet on the Grand National you miss out on the winner. “Of course you do, but you only miss out if you had managed to pick the winner, and for every winner there are lots of losers.”

While Gary has a certain admiration for firms such as KKR, acknowledging that “some work very well because as providers of capital they are brutal”, he goes on to cite the example of the manager of a company that had been taken over by private equity. The manager demanded he had ‘skin in the game’, in this case his home, and told his backers their partners “could sleep well at night because I can’t”. However, that perhaps grudging admiration is a still a gulf away from saying that private equity is a suitable investment class for Courtiers.

That said, when pushed, Gary is not quite prepared to rule it out completely. “Would I buy a private stake or a small business, or get involved in something of a private equity type deal? Yes, if the right deal came along, but it would need to form only a small part of the portfolio.”

For now, the proof is in the pudding. “The fact that no stake in private equity is in any of the Courtiers Funds at the moment and haven’t been for years tells its own story.” Quite.

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| Turns around failing companies improving profitability and efficiency | Loads debt onto companies and to raise cash strips company assets |

| Allows managers to focus on the business | Treats staff and company pensioners badly |

| Leverage provides potential for huge returns | High fees, secretive, avoids fair share of tax |

| Improves productivity | Preserve of the wealthy & institutional investors |

What exactly is private equity?

Private equity is a term that refers to a particular form of investing capital in companies.

Private equity firms raise pools of capital from investors, which they then use to invest in both public companies, which they then take private, as well as in private companies.

Private equity firms typically target companies that they believe are underperforming, ripe for expansion, or would benefit from a management buyout. Deals that lead to a public delisting often through a leveraged buyout are also popular, and have attracted the particular ire of critics.

After a limited period, (an average of 5.4 years, as reported in privateequitywire.co.uk) private equity will typically look to exit, sometimes selling to another private equity firm, a private buyer or following an IPO (initial public offering).